Animal Nations and the Doctrine of Discovery

Democracy: “Democracy didn’t come across on the Mayflower. Indeed not. Nor with the Niña nor Santa Maria. Certainly not. Democracy was here. It was in full flower. It was rampant. It was all over. All nations were free, and that includes the buffalo nation, that includes the fish nations and the nations of trees. They were all free.” — Oren Lyons (Onondaga), from The Ice is Melting, 2004.

All beings everywhere are sentient. For thousands of years, traditional elders have taught this to their children, to live in relationship to and have respect for the natural world. Since Europeans arrived on the shores of Turtle Island, the Western mindset of commodification and ownership, dominion and profit, have ripped apart Indigenous peoples’ relationships of reciprocity with the natural world, especially with the animals. What accounts for this destruction is something buried deep down in Western civilization — the false narrative of human exceptionalism.

I used to work as an editor and reporter in the nonprofit world of animal rights. I was concerned with the plight of animals, both wild and domesticated. The more I learned —-about egg-laying hens crammed into battery cages, chimpanzees incarcerated in appalling conditions for medical research, and orcas living in captivity for human entertainment — the more I asked myself where did this disconnection between human and nonhuman animals begin. What is the root of such heartlessness? If such suffering exists solely in pursuit of the almighty dollar, then how do we deconstruct today’s industrial economy? Where do we turn?

As I started working with and talking to Indigenous activists and elders, I gradually came to understand that the beaver, the wolf, and the buffalo, as well as countless other species, were Other Nations, rooted in and deeply connected to this land, and just as much victims of colonization as their human counterparts, for they, too, have been dispossessed of their homelands, massacred, their children stolen, and nearly wiped out.

The words of Osage scholar and theologian Tink Tinker helped me to see this more clearly when I heard him explain in a YouTube video why the European mindset and Indigenous thinking are so completely different. He said: “There are no bosses in the Indian world because we are all the same.” Then it hit me. The “we” in his statement extends to all humans and beyond to include the natural world, in Native nomenclature “all our relatives.” In contrast to medieval Europe, here on Turtle Island there was no hierarchy, no monarchy, no fiefdoms or serfs. Indeed, there were no beasts of burden, no domestication of other animals. Instead, there existed on this land before European contact a great “democracy of species.”

In stark contrast, so much of how we view animals in Western cultures is based on the idea that we are in charge. Humans rule. We’re the boss. Everyone and everything else is less. The Great Chain of Being — an elaborate hierarchical belief structure popularized by medieval Christianity and thought to come directly from God — deeply influenced the mindset of early European invaders, colonists and settlers and still resides in my country’s consciousness today.

In January 2021, on the day the Capital building was under siege, Betty Lyons, Director of the American Indian Law Alliance and a citizen of the Onondaga Nation, wrote on social media: “When America’s forefathers patterned their Government after ours they left out two significant pieces: the voice of women and the voice of Mother Earth.” Without a doubt, the same mindset that demeans people of color and women also sets itself above nature. America’s founders were deaf to the voices of others all around them. Instead of a “democracy of species,” they heard only themselves.

What follows is a brief lesson in the events that occurred when European Christians unloaded their domesticated animals from their ships on to the Indigenous lands of North America. The arrival of pigs, cattle, and horses — along with their masters — ushered in a transformation beyond belief. It all begins with the Doctrine of Discovery.

***

Terra Nullius: A Latin term meaning “land belonging to no one;” the refusal to recognize indigeneity; the handmaiden of colonization.

Don’t feel embarrassed if you’ve never heard of the 500-year-old racist, sexist, political doctrine issued by the Vatican that became the instrument of genocide and land theft in the Americas and around the world. It’s one of the best-kept secrets in world history. Borrowing a Roman law known as “terra nullius,” meaning “empty land” or “land without a master,” the Doctrine of Discovery defined the non-Christian lands of the so-called “new world” as empty, and the millions of human beings who lived here for tens of thousands of years or longer as having no rights of title to their land, only the rights of occupancy. Understanding this top-down domination that emanates from the Doctrine of Discovery is, in part, the work of unraveling the trauma of colonization and decentering the myth of white supremacy and human exceptionalism.

The colonization of the Americas, New Zealand, Australia, India and much of Africa quickly followed, along with the taking of natural resources and the enslavement of human beings for free labor. In 1823 the doctrine became legal precedent in the United States. And just in case you thought that was then and our laws don’t work that way any more, the doctrine was cited as recently as 2005 by the US Supreme Court as reason to deny the Oneida Nation’s attempt to regain sovereignty over lands they purchased within their historic reservation.

What sort of animals did the Spanish and Portuguese bring to these “lands without a master”? Cattle, sheep, horses, and pigs. All livestock. Somebody’s property. Often notched on the ear or branded. No “democracy of species,” that’s for sure. What was it like to have been one of the hundreds of animals stowed aboard the second sailing of Christopher Columbus’ fleet in 1493, or to have been one of the pigs Hernando de Soto brought to Tampa Bay, Florida in 1539? Those that survived the three-month journey and found themselves rooting in the forest or grazing near soldiers’ camps unwittingly caused the spread of pathogens such as anthrax, brucellosis, trichinosis, and tuberculosis to which the Indigenous populations had no immunity. The consequences of these germs—plus viruses such as smallpox and influenza— was the single most devastating event to shape the conquest of the Americas. Estimates on deaths of Indigenous people range up to 90% of the population during the 16th century.

***

Colonus: Latin for farmer, cultivator, tiller, inhabitant. Root of the words colonization, colonial, and colonist.

Illustrations by : Wolf, Joseph.

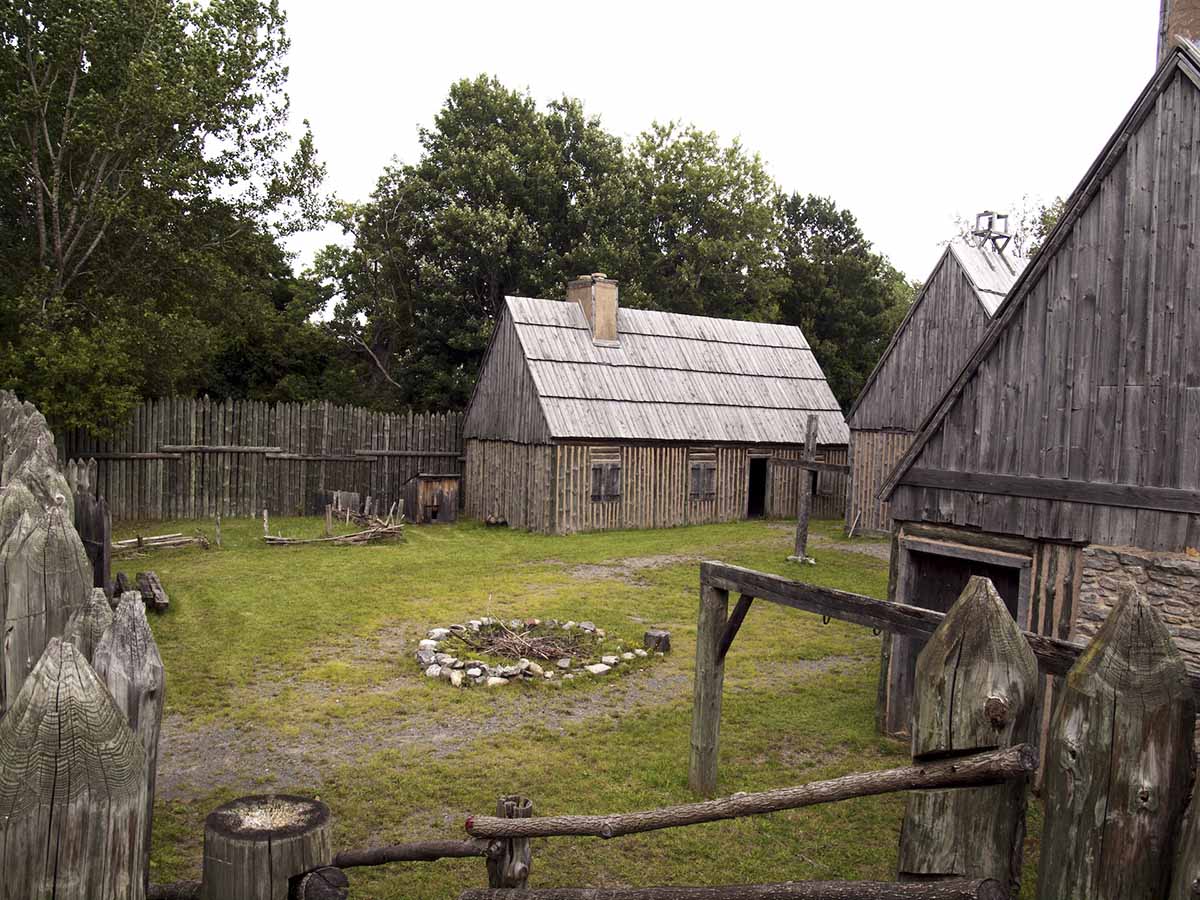

According to European tradition, farming is the backbone of civilization. In middle and high schools across the country this is often taught as fact, when in reality, farming in many ways is the backbone of colonization, not civilization. Hardly is it ever taught that these pigs and cattle and milking cows played a far greater role in uprooting Indigenous lifeways than the colonists themselves. The English and Dutch brought cattle and pigs to settlements throughout the eastern seaboard where they let them graze freely and roam quite far. This laissez-faire approach to livestock husbandry was a source of constant disputes between the Indigenous and the colonists, often escalating into violence. To make hunting easier, Native peoples burnt lands near their towns and villages to create a fresh layer of growth that would attract deer, elk and other grazing animals, but cattle often beat the wildlife to it. Pigs especially caused havoc. They scoured through berry patches and gardens, smashed up clam beds and ate all the acorns, disrupting Native peoples’ traditional food sources and contributing to food scarcity.

The reason Europeans went to all the trouble of transporting and raising livestock, instead of hunting indigenous geese, deer, pheasant, elk, rabbit, etc. in the “new world,” goes much deeper than dietary preferences. It was a lot of hard work. So much work that Native people resisted becoming farmers despite their colonist neighbors encouraging them to do so. Why should they raise livestock and grow vegetables in rows of tilled fields when they had already developed far easier ways of gathering, planting, harvesting and hunting?

For the colonists, ownership of their pigs and cattle was a way of demonstrating their perceived superiority over Indigenous ways of life. Dominion over the animals was something they considered natural and divinely sanctioned. Owning animals was a sign of wealth and status, a criteria for being civilized, no matter how much abuse the owners meted out to the animals under their control. The more farmed animals a wealthy English male landowner had, and the fatter they were, the higher his status. Milking dairy cows was considered proper women’s work, while men tilled the soil and tended the livestock. Native men, whose traditional roles were hunters, and Native women, whose traditional roles included gardening, didn’t fit the mold colonists desired. Cattle and pigs literally preceded the colonists’ taking of Indigenous lands and played a far greater role in forcing Indians off their lands than is commonly acknowledged.

No one knew this better than Thomas Jefferson. In 1803, as President of the United States, he secretly wrote a letter to Congress requesting $2,500 to fund an exploratory trip deep into Indigenous lands throughout the Great Plains and the Pacific Northwest, an expedition that would come to be know as the Corp of Discovery journey led by Lewis and Clark. Jefferson knew that Native nations in these territories were highly unlikely to enter into treaty relationships or consent to the sale of their lands. He also understood the advantageous role that livestock farming played in tearing Native peoples away from their lands and away from the animals that sustained them. Here is an excerpt from that letter in which he urged Congress to see the foresight of encouraging Native peoples to:

“… abandon hunting, to apply to the raising stock, to agriculture and domestic manufacture, and thereby prove to themselves that less land and labor will maintain them in this, better than in their former mode of living. The extensive forests necessary in the hunting life, will then become useless, and they will see advantage in exchanging them for the means of improving their farms, and of increasing their domestic comforts.”

Both then and now, livestock farming pushes everything in its way aside, leaving no room for forests, fish, or wildlife, and in the last two centuries, creating dead zones at sea, polluting rivers and emitting greens gas emissions. What follows next are brief histories of animal species indigenous to America, telling how their ties with Native Americans have been severed and in many cases how these bonds are being restored.

***

Mitakue Oyasin: A Lakota prayer meaning “we are all related.” This includes the winged, the finned, the two-legged, the four-legged, the plant nations, and the crawling beings.

Some of the species that Indigenous cultures feel the closest kinship with and hold most sacred are the same ones Western science defines as keystone species. Like the name implies, these species play an outsized role in maintaining the health of ecosystems. The Gwich’in of the Arctic are deeply connected to caribou. To the Plains Indians, it is the buffalo. The Tlingit, Chinook, Haida and many more Pacific Northwest tribal nations have such strong bonds with salmon they call themselves, and the fish, Salmon People. According to many Native traditions, if these sacred relationships are destroyed, the world falls out of balance. Perhaps that’s where we are now — living in a world that has fallen seriously out of balance.

Beaver

Beaver were among the first to be killed for the profits made from the sale of their fur when trappers from France and England arrived on Turtle Island. Other animals included fox, marten, mink and otter, but especially beavers. To the Native Americans, their skins were currency, worth beads, metal pots, fabrics, guns and ammunition. To the French and English trappers, their skins were highly valued as the raw material required to make fashionable felt hats popular throughout Europe and western Russia. Influenced by the insatiable market for beaver skins, European trappers kept moving west to find and kill more beavers.

The beaver’s story is a difficult one. It is often told to highlight how Native people were complicit in the outright commodification of animals. But it’s not that simple. Indigenous Traditional Knowledge instructed generations of hunters to take only what they needed, to behave respectfully so not to offend the animal’s spirit, and to share the animal’s gifts in a respectful manner with human and non-human beings. However, a multitude of factors conspired against them over the initial course of colonization fostering their dependence on manufactured goods, including alcohol. The transition away from traditional lifeways rocked Indigenous communities to their core. By the beginning of the 20th century, 40 to 60 million beaver were dead and long-held traditions lost.

Today, the beaver is making a comeback. As a keystone species beaver create freshwater wetlands, improve water quality and salmon habitat, and mitigate the effects of drought and flooding. The Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, the Tulalip Tribe, the Cowlitz Indian Tribe, and the Yurok Tribe are all currently working to restore beaver populations. Tribal members recognize these sites as “sacred centers,” their ancestors’ name for the beavers’ home, because it is a place where fish, heron, turtles, otters, frogs, insects, owls, and ducks all live together, restoring balance to the world.

Sturgeon

Sturgeon have been here long before the dinosaurs. They have proven their resilience for hundreds of millions of years thriving within their water territories. Native legends “tell of rivers so full of sturgeon that a person could walk across the water on the backs of the fish.” To the Menominee, Ojibwe, Potawatomi and other Native peoples the sturgeon ensured they would survive another year, as fishermen caught them swimming to their birthplace to spawn every spring. These massive fish, weighing 400 to 800 pounds, and known to live well over 100 years are credited for having saved the colonists who arrived in Jamestown in 1609 from starvation that winter season.

From early colonial history to today, the sacred ties between sturgeon and Native people have been broken. To white fishermen who were after trout, herring and whitefish, the sturgeon were pests, a “trash fish” whose barbels and bony plates ripped through their nets. So they slaughtered them. In the 19th century, tens of thousands were killed by commercial fishermen. Their dried but oily carcasses were stacked like logs of firewood along the shores to be later used for fuel on steamships. When the lucrative business of selling sturgeon roe as caviar took off in the late 1800s, it wasn’t long before populations of this ancient fish were in catastrophic decline. Today, all 26 species are slipping towards extinction due to pollution, dams, overfishing, and habitat loss.

California Condor

With a wingspan of over 9 feet, condors fly the highest of all birds and for this reason the Yurok see them as spiritual beings and entrust them to carry their prayers to the Creator.

“Condors are necessary for our world be be whole” said Tiana Williams-Clausen, tribal member of the Yurok Nation and Director of the Yurok Tribe Wildlife Department. Her work raising and releasing condors bridges Western science and Traditional Indigenous Knowledge in remarkable ways. “A lot of the things that impacted them, also impacted us as tribal people,” she said at a recent wildlife conference and went on to explain their similar fates: loss of homeland, massacres, loss of large mammals such as deer, bear, elk, and whales. Even exposure to toxins such as lead in bullets, poison, and the insecticide DDT parallels the Yurok peoples struggles with alcohol, drug addiction, and disease, she added.

Settlers in search of gold first rushed into Yurok territory around 1849. Logging followed, devastating the forests. Miners committed massacres that were genocidal in scale. Missionaries and government agencies forced Yurok children into residential boarding schools. During this war of extermination, both Yurok and condors were close to being eliminated. In 1910 the Yurok population was under 700. Today, they are the largest tribe in California with more than 5,500 members. In 1982 only 22 condors were left. Today, their population is 537 with more than half living in the wild.

Buffalo

When the US cavalry could not defeat the Plains Indians in battle, they came back to attack their relative, the buffalo. The horror that happened next came out of the greed of market hunters funded in large part by the US federal government. In the late 19th-century, over a period of three decades, buffalo populations in the United States plummeted. After they were shot and killed, their bodies were striped of their fur and their tongues cut out, leaving the rest to rot and stink on the prairie lands. “Every buffalo dead is an Indian gone.” The windigo words of Colonel Richard Dodge, 1867. In 1884 only a few hundred remained, finding refuge in Yellowstone National Park.

Once as many as 60 million roamed across North America. Today, the last pure wild buffalo herd in the United States numbers around 5,000 individuals that reside in Yellowstone National Park. The rest, approximately 500,000, are raised as livestock and have been crossbred with cattle in unsuccessful attempts to create a hardier cow. Like cattle, they will spend their last days in feedlots. In his book American Serengeti, the environmental historian Dan Flores shared a story told to him several years ago by Fred Dubray (Cheyenne River Sioux), one of the founders of the Intertribal Bison Cooperative. Dubray said when the cooperative was just getting started some people got together to discuss ideas about how to bring buffalo back to reservations. A Lakota elder, a woman, quietly spoke up and said, “Best you ask the buffalo if they want to come back.” So they held a ceremony and did just that. What did the buffalo say? “They said they wanted to come back,” Dubray told Flores, “but …they didn’t want to come back and be cows. They said they wanted to be buffalo. They wanted to be wild again.”

Throughout Indian Country, in growing numbers, buffalo are heading home renewing old bonds — Wind River Reservation in Wyoming, Blackfeet Indian Reservation in Montana, Rosebud Reservation in South Dakota, Fort Peck Reservation in Montana, and more.

***

Justice: “We seek justice, not just for ourselves, but justice for the whole creation.” — Audrey Shenandoah (Onondaga)

In 2001, I had the honor of working with environmental activist and Lakota language teacher Rosalie Little Thunder (Sicangu Lakota) as we fought together to try to close down one of the world’s largest hog factories being built on sacred Lakota lands in South Dakota. With Rosalie as my guide, I visited Rosebud Sioux Reservation just as Bell Farms was trying to get an enormous hog confinement facility built as fast as possible, pushing the deal through without a complete Environmental Impact Statement. More than 98 percent of farmed pigs in the United States are raised in overcrowded warehouse-sized buildings called CAFOs (confined animal feeding operations), where piglets mature into adults without ever seeing the outdoors and enormous quantities of water flush the manures away into so-called “lagoons.” This was what Bell Farms was forcing on Indian Country, adhering to a form of capitalist economics that calculates the pollution of the land, the water, and the endless suffering of animals as inconsequential compared to the mass production of pork for profit. We were seeking justice not just for the Lakota, but for the whole creation: the land, the water, and the pigs.

It took five years to stop the construction of Bell Farms. Rosalie knew we were up against formidable forces. She had been up against them before. Years earlier she co-founded an organization called Buffalo Field Campaign, one of the few groups working to stop the annual slaughter of Yellowstone National Park buffalo for committing the crime of grazing beyond the park’s boundaries. She wanted these last wild buffalo not to disappear, and for Native peoples to have more agency in their fate.

Stories of decolonization take many forms. Recognizing the dignity of animals is a part of the narrative that’s often missing. As we worked together, Rosalie told me how the buffalo fertilize the soil with their droppings, carry seeds in their coats over long distances, and don’t stay long enough in any one place to cause damage. They break trails in the winter snow and ice, later to be traversed by elk, deer, coyote and other smaller species, and she said, all the predators benefit—the wolf, the grizzly, birds of prey—when a buffalo dies. “When we see how the buffalo functions in its ecosystem, we hold it to be sacred,” she explained. The more she spoke, the more I began to grasp the huge cultural divide between the domesticated pig trapped in industrial agriculture and the wild buffalo, struggling to stay free.

Healing these broken bonds requires the will of strong hearts. Such ways are not new. They come from a long time ago when the land had no bosses. Only relatives. When each act of restoration is an act of decolonization, it contributes to breaking down a 500-year-old edict that nearly succeeded in destroying the wisdom of the world.

“Sometimes our truth makes others uncomfortable. But it’s never ok to make anyone feel less than because of it. Nobody is higher or better than anyone else.” — Issac Murdoch, Ojibwe First Nations artist and educator

Copyright Notice

© 2023 Tracy Basile

Biography

Tracy Basile is writing a book about the lives of animals in American history. Her articles have been published in The Village Voice, Orion Afield, ASPCA Animal Watch, and more. She teaches writing at Saint Thomas Aquinas College and lives in Lenapehoking in the Hudson Valley of New York.

SUGGESTED CITATION

Tracy Basile, "Animal Nations and the Doctrine of Discovery," Doctrine of Discovery Project (3 March 2023), https://doctrineofdiscovery.org/blog/animals-doctrine-discovery/.

Share on

Twitter Facebook LinkedInDonate today!

Open Access educational resources cost money to produce. Please join the growing number of people supporting The Doctrine of Discovery so we can sustain this work. Please give today.