How we met the Doctrine of Discovery. A Maya commentary

It was an ordinary evening on October 9, 2018 when, scrolling down my mouse wheel randomly looking at posts on Facebook something suddenly caught my attention: A post launched an invitation from the Mennonite Coalition for the Dismantling of the Doctrine of Discovery to join a Christian lament in the United States. The post invited lamenting of the Doctrine of Discovery (DD) and encouraged reflection on its consequences for the lives of Indigenous Peoples today.

I am a believer in symbolic numerology and the cycles of time thanks to my Maya heritage. That is why I believe it was more than a coincidence that I came across this post on the 9th of October, just three days before the celebrations of the 12th of October, the mythical date of the so-called “Discovery of America” or the beginning of the colonization of Yóokol K’ab, the Maya world in my mother tongue.

The timing and numbers around the Lament’s post on social media definitely touched me: 3, 9 and 12 are strong numbers in the Mayan calendar. For example, number three bears a profound significance related to K’oben, the three stones in the kitchen fire meaning the heart of our home, family and community. Somehow I felt moved to contact the Mennonite Coalition.

At the same time we began to reflect on the meaning of this Lament for Mayan communities in Ka’ Kuxtal Much Meyaj, a Mayan organisation based in Hopelchen, Campeche, Mexico. Ka Kuxtal’s assembly devoted its collective work to learn more and to confront together the legacy of DD in our territories. This is how we start unveiling the colonial legacy behind this doctrine in the Mayan communities. Thus, we decided to walk together the path of joyful rebellion as our Zapatista sisters say. This is how we consensually met, confront and reject the Doctrine of Discovery.

Today, after four years of co-labour with the Mennonite Coalition, we wish to report on some of this collective learning. Due to space constraints, I will only focus on the connections between DD and the Mayan heritage, i.e. sacred sites.

Mexico’s Colonial Legacy

As we are aware, the colonial ideologies that served the purposes of colonization in the Americas such as the DD did not vanish with independence and the formation of modern States, but rather laid the foundations for the strong asymmetrical dependencies and power relations that remain in place1 between States and Indigenous Peoples.

Under the principle that the Indigenous territories were ‘empty’2 (terra nullius) and that by virtue of their ‘discovery’ the colonial powers hold territorial sovereignty on top of the ancestral occupation of Indigenous Peoples: “Discovery [is] the original foundation of titles to land on the American continent as between the different European nations by whom conquests and settlements were made here.”3 Consequently,it is taken for granted that land ownership is handed over from the colonial powers to the States by virtue of their independence: “…fee title [ownership] to the lands occupied by Indians when the colonists arrived became vested in the sovereign–first the discovering European nation and later the original States and the United States…“4 Such is the case in Mexico, where the sovereignty of the State was imposed upon the Maya peoples in a manner similar to how the sovereignty of the Crown was imposed in the past. For the Mexican State, the territories dominated by the Spanish Crown become the property of the Nation by virtue of its political independence.5 Article 27 of the Mexican Constitution states:

“The ownership of the lands and waters included within the limits of the national territory corresponds originally to the Nation, which has had and has the right to transmit the domain of them to private individuals, constituting private property” (My translation, Cámara de Diputados 2001).

From emblematic court cases in North America and Australia, it has become clear that the DD and terra nullius continue to underpin state legal frameworks. Its impacts include the continued usurpation of Indigenous Peoples’ lands, territories and resources, the destruction of their political and legal institutions, and the discriminatory practices aiming to destroy Indigenous cultures, among others (see John 2014).

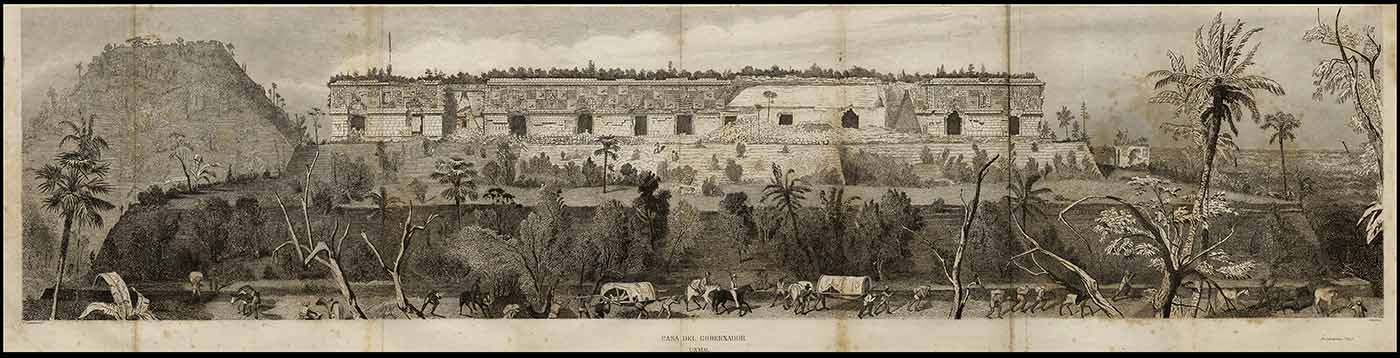

As this is the case in Mexico due to a narrow interpretation of Article 27 of the Constitution, this has translated into the dispossession of the Maya Peoples of their Sacred Sites, an integral part of their ancestral territories. Therefore, it is also taken for granted that the archaeological sites (e.g. Uxmal, Chichen Itza, Calakmul), namely the Sacred Sites and cultural heritage of the Maya, allegedly become the property of the Mexican State and must solely be managed by State institutions, leaving the Indigenous institutions out in the cold. Such an interpretation is reaffirmed by the Mexican Monuments Law (MML): “Movable and immovable archaeological monuments are property of the Nation, inalienable and imprescriptible” (Cámara de Diputados 2018: Art. 27, my translation). MML goes further:

“Archaeological monuments are the movable and immovable goods, product of cultures prior to the establishment of the Hispanic culture in the national territory, as well as the human remains, flora and fauna, related to those cultures” (Op. Cit.: Art. 28, my translation).

As we can see, it is not only the narrow interpretation of Article 27, but the impacts of DD and terra nullius in juridical principles that leads the Mexican State to self-legitimize as administrator, owner, and the ultimate decision-making authority over Indigenous territories and heritage.

The Doctrine of Discovery, terra nullius and the Other in motion.

The extent to which the DD impacts heritage practice and policy-making in Mexico require more scrutiny since DD’s linkage with other doctrines-ideologies is not obvious at first glance. The historical criticism below helps to uncover the links that set in motion a racist and supremacist ideological machinery that ends up impacting the Maya heritage management.

As we know, based on the assumed racial, cultural and religious superiority of the colonial powers, the Doctrine of Discovery was legitimized by the Roman Catholic church by means of the papal bulls Dum diversas (1452), Romanus Pontifex (1455), and two Inter caetera (1493 and 1494). By virtue of their Roman ecclesiastical legitimacy, they justified the confiscation of territories in possession of the Indigenous Peoples of the Americas and their subsequent domination during the so-called “Age of Discovery” (Robertson 2005). The second Inter caetera,6 issued by Alexander VI on May 4, 1494, follows the ideological tradition of Dum diversas and Romanus Pontifex in defining non-Christian nations as enemies, “heathens”, “pagans”, “gentiles”, “infidels”, “barbarians” and “savages”: “…that the barbarian nations be subdued and reduced to the Christian faith”. This bull also refers to terra nullius meaning “undiscovered” lands: “…remote and unknown islands and firm lands, hitherto undiscovered by anyone, …”. On the basis of the dehumanization of the native peoples, the Roman church thus granted the ownership of the “discovered” lands to the Catholic kings Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile.

However, the juridical concept of nullius (or nullus) applied not only to the territories but also to the people(s) who had occupied for millennia the allegedly discovered lands. Nullus Persona, meaning non-Christian, pagan, infidel or unbaptized inhabitants, is a necessary premise for the Doctrine of Discovery. Otherwise, the “discovery” would be questionable if native people were legally recognised at first glance by the Spanish Crown. Burke Aaron Hinsdale (1837-1900) states it as follows:

“If it is conceded that res nullius is the property of the one who finds it, that an infidel is nullius [non-existent]; that the wild American [Indigenous] is an infidel [nullius or non-existent], then the reasoning is complete” (Gonnella Frichner 2010).

In Mesoamerica the idea of Nullus Persona is underpinned by paganism-barbarism attributed by the Spaniards to native peoples. The construction of a barbarian ‘Other’ is fueled by allegations of cannibalism and human sacrifice by Hernan Cortés and friars, such as Diego de Landa, from the early stages of colonization.7 As such, the Doctrine of Discovery, terra nullius and Nullus Persona (a juridical “disabled” Indigenous ‘Other’: barbarian and infidel) had been set in motion for the colonial project in the Americas aiming at legitimizing a constructed status of moral and racial superiority for European Christians and their authorities.

.png)

The Doctrine of Discovery in colonial Yucatan

As mentioned above, Diego de Landa’s Relacion8 draws a “barbarian” image of the Mayas of the Yucatan Peninsula by alluding to human sacrifice and cannibalism. In Chapter III, the friar cites the Spanish shipwrecked sailors Aguilar and Guerrero, who arrived in the Maya region before him:

“That these poor people came into the hands of a bad cacique, who sacrificed Valdivia and four others to their idols and then made banquets (with the meat) of them to the people, and that he left Aguilar and Guerrero and five or six others to fatten up, who broke the prison and fled through some mountains…” (Landa 2005, C. III., my translation).

Landa’s Relacion makes the connection between barbarism and paganism in Chapter XLIII, where human sacrifice is described, as an inherent Mayan religious practice guided by evil:

“…After killing in their towns, they had those two decomulgated sanctuaries of Chichen Itzá and Cuzmil where an infinite number of poor people were sent to sacrifice or take down the one, and to take out the hearts of the other; …” (Op. cit., my translation).

In several cases the description matches to rituals, ceremonies and self-sacrifice (blood-letting). Yet, it is often confused with human sacrifice, in its most negative sense. It is to be expected that the friar would attempt to win the favor of his audience through his narrative. Let us remind that his targeted audience was made up of ecclesiastical and administrative authorities, namely the Council of the Indies that requested the bishop to justify his inquisitorial activities in New Spain including torture (Tedlock 1993) and the burning of sacred codices in Mani, Yucatan, which Landa himself details in his Relacion.9

The sacrifice, as a ritual act, that Landa attributes to the Maya is linked with evil and the devil and sets in motion paganism and barbarism in a single narrative. The constant repetition of keywords such as sacrifice10, evil, demon, idolatry, etc., is delivered in his Relacion in such a way that even today induces a psychological predisposition of rejection of the othered Maya. Noteworthy, its impact is still far-reaching in the XXI Century (Abbott 2020).

Landa’s account does not allude to terra nullius, even though it is an essential link to the Doctrine of Discovery because his case before the Council of the Indies was about the abuses committed in his inquisitorial enterprise rather than land disputes. While terra nullius does not play an important role in Landa’s argument, it did for both the Spanish crown at the beginning of colonization and for the ‘encomenderos’ who settled in Maya lands over the next three centuries, as we will see below.

The Doctrine of Discovery and Maya heritage in the 17th - 19th centuries

Colonial testimonies in Yucatan show allegations of paganism-barbarism in the context of land concessions, claims or disputes, in such a way that these testimonies can be instrumental to legitimize the occupation of so called idle lands (tierras ociosas). Indigenous territories, however, housed pre-colonial cities, buildings and temples where rituals were continuously performed in spite of the Inquisition. The testimony of explorer and lawyer John Lloyd Stephens - about his visit to the Yucatan Peninsula between 1839 and 1842 - illustrates how the idea of paganism was invoked in a land litigation process in the 17^th^ Century. Stephens alludes to historical documents with which Captain Lorenzo de Evia petitioned the Spanish king to grant the land around Uxmal.11 This procedure apparently begins on May 12, 1673, according to Stephens’ testimony. In these times, more than a century after Inter caetera, the land ownership situation was much more complex in the Maya region and a good number of Indigenous people owning property titles could already be counted (Bracamonte y Sosa 2003: 151-189).12 However, in order to mobilize the land concession in his favor, de Evia used paganism in his argument:

[It could result in a] “…very great service to God our Lord, because with that establishment it would prevent the Indians in those places from worshipping the devil in the ancient buildings which are there, having in them their idols, to which they burn copal, and performing other detestable sacrifices, as they are doing every day notoriously and publicly” (Stephens 1843: 323).

It should be remembered that in the 17th century the Inquisition was still in force in the Maya region13 and that the persecution of idolatry (paganism) mobilized the ecclesiastical juridical system, which could nullify the juridical personhood of the charged (thus becoming Nullus Persona) if they were found guilty (as lawyer Stephens himself outlined, op. Cit. 1843:28). Fear of Inquisition could have been a decisive factor for the Maya communities to waive any property claim.14

Despite this, a local inhabitant, Juan Can, claims his right to these lands based on various documents and his Maya ancestry (Stephens Op. Cit.: 323-324). We know little about Juan Can. We can deduce, however, that his socio-political position within the colonial regime would not allow for egalitarian litigation. Although the Spanish Crown since 1560 had ordered to protect Indigenous communities’ access to land (see footnote 24 in Carrera Quezada 2015), a large majority lived in slavery conditions and of strong asymmetric dependence on “hacendados” and clerics (Farris 2012; Bracamonte y Sosa 2001).

In contemporary Mexico a legalized and institutionalized dispossession of Maya heritage exists and it is based on the Doctrine of Discovery’s principles.

At present, Sacred Sites such as Uxmal, Chichen Itza, Calakmul, etc., are banned to the Maya. The Mayas have to pay a fee to access these sites just like any national tourist. In 2018 Ka’ Kuxtal had to ask for permission from INAH, the state heritage institution, to be able to perform a ritual at the Sacred Site of Dzibilnocac (Dzibil Noh Ak), in Hopelchen. In terms of Self-Determination, this means that Maya peoples do not enjoy the right to self-manage our heritage. The State, self-legitimized as owner, dispossesses us of it with its laws and policies, which in turn, perpetuate the notion of nullius persona by legally disabling contemporary Maya from (our own) heritage managenment.

Closing words

No celebration in 21st century Mexico better reflects the legacy of the DD than the celebrations of 12 October. According to the official narrative, it commemorates the “encounter” that “gave rise to a fusion of cultures and the birth of a Hispano-American civilization”.15 Although Mexico recognizes that other countries in the Americas have chosen to vindicate the position of Indigenous Peoples and commemorate the “Day of Indigenous Resistance” on 12 October, in its official discourse it finds a greater affinity with a romantic narrative around the “meeting of two worlds”.

Although the word “discovery” is disappearing from the official vocabulary, heritage policies in particular are still permeated by the DD as we have discussed in this article. We are still far from triggering a collective lament from educational and Christian institutions in Mexico. The future, however, looks hopeful, as we continue walking the path of joyful rebellion initiated by Ka’ Kuxtal in alliance with the Mennonite Coalition to confront and dismantle the Doctrine of Discovery.

Bibliography

-

Abbott, J. (2020) ‘Outrage as Guatemalan Maya spiritual guide is tortured and burned alive’, the Guardian, 10 June. Available at: http://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jun/10/guatemalan-maya-spiritual-guide-tortured-burned-alive (Accessed: 3 September 2021).

-

Arens, William (1979) The Man-Eating Myth: Anthropology and Anthropophagy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

-

Augustine, Sarah (2021). The Land Is Not Empty: Following Jesus in Dismantling the Doctrine of Discovery. MennoMedia.

-

Bonfil Batalla, Guillermo (1987) México profundo: Una civilización negada. México: SEP-CIESAS.

-

Bracamonte y Sosa, Pedro (2001) ‘Apuntes sobre la tenencia patrimonial de la tierra entre los mayas yucatecos y sus implicaciones en el análisis de la organizaciónn social’, in Escobar Ohmstede, A. and Rojas Rabiela, T. (eds) Estructuras y formas agrarias en México: del pasado y del presente. Mexico: CIESAS, pp. 45–68.

-

_____, (2003) Los Mayas y la tierra: la propiedad indígena en el Yucatán colonial. México: Miguel Angel Porrúa.

-

Cámara de Diputados, H.C.D.L.U. (2001[1917]) ‘Constitución Política de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos [CPEUM]’. Secretaría General.

-

_____, (2018[1972]) ‘Ley Federal sobre Monumentos y Zonas Arqueologicos, Artisticos e Historicos (LFMZAAH). México’. Secretaría General.

-

Carrera Quezada, Sergio, (2015) ‘Las composiciones de tierras en los pueblos de indios en dos jurisdicciones coloniales de la Huasteca, 1692-1720’, Estudios de Historia Novohispana, 52, pp. 29–50.

-

Casanova González, Pablo, (1991) La democracia en México. Segunda. México, D.F.: Ediciones Era.

-

_____. (2006) ‘Colonialismo interno [una redefinición]’, in Boron, A. A., Amadeo, J., and González, S. (eds) La teoría marxista hoy. Problemas y perspectivas. Buenos Aires: CLACSO, pp. 409–434.

-

_____. (2017) Explotación, colonialismo y lucha por la democracia en América Latina. México, D.F.: Ediciones AKAL.

-

Chuchiak, John F. (2002) ‘Toward a Regional Definition of Idolatry: Reexamining Idolatry Trials in the “Relaciónes De Méritos” and Their Role in Defining the Concept of “Idolatria” in Colonial Yucatán, 1570-1780’, Journal of Early Modern History, 6(2), pp. 140–167.

-

Farriss, Nancy M.(2012) La sociedad maya bajo el dominio colonial: la empresa colectiva de la supervivencia. Primera. Translated by María Palomar. México: CONACULTA.

-

Gonnella Frichner, Tonya (2010) Preliminary study of the impact on indigenous peoples of the international legal construct known as the Doctrine of Discovery. Report by the Special Rapporteur E/C.19/2010/13. New York: United Nations, p. 22. https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/677571

-

Jansen, M. E. R. G. N. and Pérez Jiménez, G. A. (2019) ‘Deconstructing the Aztec Human Sacrifice’, Incidental paper. Center for Indigenous America Studies.

-

John, Edwards, (2014) Study on the impacts of the Doctrine of Discovery on indigenous peoples, including mechanisms, processes and instruments of redress. Outcome of the study submitted to the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues at its thirteenth session. E/C.19/2014/3. New York, USA: United Nations, p. 11.

-

Landa, Diego de, (2005) Relación de las Cosas de Yucatán. Primera Reimpresión. México, D.F.: Monclem Ediciones.

-

Restall, Mathew and Chuchiak, John F. (2002) ‘A Reevaluation of the Authenticity of Fray Diego de Landa’s Relacion de las cosas de Yucatan’, Ethnohistory, 49(3), pp. 651–669.

-

Robertson, Lindsay G. (2005) Conquest by Law: How the Discovery of America Dispossessed Indigenous Peoples of Their Lands. New York: Oxford University Press.

-

Schüren, Ute, (2017) ‘Pueblos indígenas y migración en la península de Yucatán durante la época colonial’, INDIANA, 34(2), pp. 55–84.

-

Stavenhagen, Rodolfo, (1963) ‘Clases, colonialismo y aculturación: ensayo sobre un sistema de relaciones interétnicas en Mesoamérica’, América Latina. Revista del Centro Latinoamericano de Investigaciones en Ciencias Sociales, año 3(4).

-

Stephens, John L. (1843) Incidents of travel in Yucatan. New York, USA: Harper & Brothers. Available at: http://archive.org/details/travelinyucatan01step (Accessed: 25 April 2012).

-

Tedlock, D. (1993). Torture in the Archives: Mayans Meet Europeans. American Anthropologist, 95(1), 139–152.

Footnotes

-

On colonialism, internal colonialism, global colonialism and the complex social, cultural, political, military and economic dependencies in independent Mexico see Bonfil Batalla 1987; Casanova 1991, 2006 and 2017; and Stavenhagen 1963. ↩

-

This commentary is inspired by Augustine 2021. ↩

-

Case Johnson & Graham’s Lessee v. McIntosh in 1823, in the United States. See a summary and comments of the legal case at https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/21/543/ ↩

-

Sherrill v. Oneida case. See footnote 1 of this case review at https://www.law.cornell.edu/supct/html/03-855.ZO.html#FN1SRC. Notice that the concept of Original States refers to Independent States including the United States of America. ↩

-

The territories properties of the Nation are, however, those whose legal dominion was obtained by alluding to the Doctrine of Discovery and terra nullius. ↩

-

A digital version of the original document is available at the database of Archivo General de Indias: http://pares.mcu.es/ParesBusquedas20/catalogo/show/17160. I am relying on the Spanish translation at http://www.artic.ua.es/biblioteca/u85/documentos/1572.pdf ↩

-

Cannibalism and, more recently, human sacrifice as an inherent practice of the religiosity of native peoples has been contested on the basis of the overwhelming scarcity of first-hand witnesses (Arens 1979, Jansen & Pérez Jiménez 2019). ↩

-

It is worth noting that Restall & Chuchiak (2002) have questioned the order of the chapters and the authenticity -or Landa’s authorship- of some passages of the text. ↩

-

The bishop was sent to Spain in 1563. During his stay in the Iberian Peninsula, he apparently wrote a number of manuscripts later arranged in his Relacion (Restall & Chuchiak 2002). ↩

-

“Sacrifice” is used 36 times, and in 6 of the 52 chapters appears in heading. ↩

-

A ceremonial site now included in the UNESCO’s World Heritage List ↩

-

Bracamonte y Sosa (Op. Cit.:152) mentions at least five mechanisms of land alienation that functioned until the middle of the 19th century. Interestingly, Bracamonte y Sosa (2001) illustrates with some examples that property transmission among Maya families took place with less gender restrictions. That is, it was inherited from mothers to daughters as well. For an extended description of the socio-political situation in the Yucatan Peninsula in colonial times see Bracamonte y Sosa 2003 and Farris 2012: 51-86. ↩

-

In 1686, only 100 km away Uxmal, the local priest of Yaxcabá denounced a case of “idolatry” (see Chuchiak 2002). ↩

-

It could also be the case that they were inhabitants of nearby communities who, despite the relocations, ordered by the Crown in 1568 (see footnote 26 in Carrera Quezada 2015), made pilgrimages to Uxmal to perform rituals. Colonial mobility-migration in the Yucatan Peninsula was complex as we see in Farris 2012: 269-300 and Schüren 2017. ↩

-

https://www.gob.mx/siap/articulos/dia-de-la-raza-y-el-nuevo-mundo?idiom=es ↩

SUGGESTED CITATION

Manuel May Castillo, "How we met the Doctrine of Discovery. A Maya commentary," Doctrine of Discovery Project (2 February 2023), https://doctrineofdiscovery.org/blog/doctrine-discovery-maya-commentary/.

Donate today!

Open Access educational resources cost money to produce. Please join the growing number of people supporting The Doctrine of Discovery so we can sustain this work. Please give today.