Uncovering the Invisible: The Doctrine of Discovery, its Impact on the Brazilian Indigenous Peoples, on the environment and how it continues to shape the Brazilian landscape today: English

Abstract

Despite being a tool of colonization and imperialism worldwide, the Doctrine of Discovery’s importance and influence has been overlooked in Brazilian literature and studies. This article examines the Doctrine’s impact on the Brazilian Indigenous people and environment, highlighting the need to acknowledge and understand the effects and manifestations of the Doctrine of Discovery in Brazil. It explores intersections of the Doctrine with Indigenous rights and sovereignty. It argues that understanding the Doctrine is essential to move forward respectfully and sustainably with Indigenous people and the environment.

Keywords:

Doctrine of Discovery, Brazilian Literature, Indigenous Peoples, Amazon Forest, Yanomami, Environment, Colonization, Imperialism, Rainforest, Indigenous Rights, Sovereignty, Tordesillas Treaty

Introduction

The Doctrine of Discovery has long been used for colonization and imperialism worldwide, yet its importance and influence have been largely overlooked in Brazilian studies.

European nations used this international Law during the Age of Exploration to justify their colonization of lands outside of Europe. Based on the idea that Christian nations had the right to claim lands that Christians did not inhabit, the Doctrine justifies the displacement of Indigenous peoples from their traditional lands and the seizing their resources. (Miller, 2011)

Information about the Doctrine in Brazilian History books, pedagogical and academic publications, articles, and research is close to none, and the case is the same for information available in Portuguese.

Studies by John Hemmings, anthropologist, historian and one of the world’s experts on Brazilian Indians and the Amazon environment, are available in Portuguese and accessible to Brazilians. He wrote extensively about Brazilian Indigenous people and their domination and oppression since their first encounters with Europeans. Except for his discussions about the Treaty of Tordesillas, Hemmings does not refer to the influence of the Doctrine.

It is as if the Doctrine of Discovery never existed below the Equator, and the Tordesillas Treaty, one of its leading technologies, was merely about land demarcation with no further manifestations.

Some of the most comprehensive works directly referring to the Doctrine of Discovery manifestations in Brazil are publications by Robert Miller. His work with Micheline D’Angelis, “Brazil, Indigenous Peoples, and the International Law of Discovery” (Miller & D’Angelis, 2011), is available in English.

In this article, I include recent and concrete cases that reflect the Doctrine’s power of epistemological colonialism manifesting itself in Brazilian life as it seeks to impose a particular set of values, beliefs, and knowledge systems on a colonized population.

A Eurocentric, white supremacist concept, the Doctrine is frequently used to justify the colonization of Indigenous lands and the exploitation of Indigenous peoples. In a country colonized by the Portuguese, Brazil, discussions about the Doctrine remain inexistent. This silence has allowed the Doctrine’s manifestations and effects to remain present, unquestioned, untouched, and ignored.

This article explores such invisibility and aims to identify connections between the principles of the Doctrine of Discovery and the ongoing violence against indigenous people in Brazil, together with the devastation of the Amazon Forest and its catastrophic environmental effects.

Manifestations and effects of the Doctrine must be included in the Indigenous debate; otherwise, misinformation and dismissal of crucial factors will contribute to epistemic violence resulting from reductionist approaches and interpretations of Brazil’s decades-long ongoing violence against Indigenous people.

An example is attempting to link the Canadian Truth and Reconciliation Commission to a 2012 Brazilian National Truth Commission (CNV) as if the Brazilian Commission represented any attempt to deal with the violence against Indigenous in Brazil. It is not the case. This is one of the situations when misinformation results from a lack of dealing with the reality that has devastated Indigenous populations in Brazil for decades, if not centuries. Besides, there is no discussion of the Doctrine’s manifestations and effects in each country and context.

In this case, comparisons between the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in Canada and the National Truth Commission in Brazil reduce the century-old historical factors present in the ongoing violence against Indigenous people to an event that hides the truth behind time and space constraints, reinforcing the epistemic violence (Fricker, 2011) that victimizes them. In addition to the fact that the Brazilian Commission (CNV) was not created to address Brazil’s ongoing violence against Indigenous people, it is essential to understand that a truth commission is focused on the past rather than ongoing events (Hayner, 2010). In the case of Brazilian Indigenous peoples, violence never ended, and it is an ongoing fact.

Recognizing Indigenous people’s unique experiences and context in different countries is crucial.

Reductionist comparisons reflect the continuity of epistemological colonialism, which creates misconceptions and hides and silences the connections of the Doctrine of the Discovery to current events.

This article is not about current events in the Amazon rainforest, denouncing the current precarious conditions of the Yanomami as their land is invaded and exploited.

However, it refers to such events as a way of shedding light on the manifestations of this International Law’s principles still present today in the justifications for removing indigenous peoples from their land, their subjugation and attempts to eliminate them.

The Doctrine principles are at the roots of the tragedy that unfolds in the Amazon today, as the Yanomami people struggle to survive while facing what is seen by many organizations as genocide (Philips, 2023)(Reuters, 2023) (Sassin, 2023)(Miller, 2015).

Recognized as the world’s richest biological reservoir, containing several million species of all life forms, many not even recorded by science yet, the Amazon Rainforest comprises 40 percent of Brazil’s total area.

On January 20, 2023, five hundred and twenty-three years after the arrival of the Portuguese in the land to the east of the Treaty of Tordesillas, today Brazil, the world witnesses the miserable conditions under which the Yanomami people try to survive in the Amazon Forest.

The tragedy unfolding in the Yanomami territory shows adults and children in severe malnutrition, starving as fishing, farming, and hunting became impossible due to river contamination with mercury used for mineral extraction. They are perishing from all kinds of diseases brought by illegal mining. Rape and murder of Yanomami children by invaders, the advance of drug traffic and violence against those who challenge the status quo is rampant in their land.

Powerful machinery and automatic weapons are used to dislocate, intimidate and kill Yanomami indigenous people and their defenders. The murder of British journalist Don Phillips and Brazilian indigenous expert Bruno Pereira in June 2022 under the orders of a fish trader leading an illegal fishing scheme in the Amazon followed the murder of many indigenous people in the Yanomami territory.

The Yanomami reserve is home to around 28,000 Yanomami. Approximately 10 million hectares are home to 371 hard-to-reach communities in the dense Amazon rainforest.

According to research by the Instituto Socio Ambiental (ISA) (ISA, 2022), they descend from an Indigenous group that remained relatively isolated for at least a thousand years. This ancient group would have occupied the area of the headwaters of the Orinoco and Parima rivers (which are currently in Roraima, Brazil). Their relationship with the Amazon rainforest and environmental preservation is directly linked to their concern for protecting the forest as part of the Yanomami’s relationship with nature.

The Yanomami people’s decimation has intensified since 2017, during the government of Jair Bolsonaro. After his defeat in the 2022 elections, the new government elected Sônia Guajajara as Brazil’s First Minister of Indigenous Peoples. She immediately started rebuilding the systems of protection unmounted by the previous president.

Guajajara, a member of Guajajara/Tentehar, graduated in Literature, Nursing and Special Education. She has a history of struggle for the rights of the original peoples and the environment.

The 2023 Ministry of Indigenous Peoples creation constitutes a milestone in the changes needed to address relations with Indigenous Peoples, from the Judiciary to Legislative and Executive Powers. It also addresses the lack of representation of Indigenous people at the roots of what some identify as friction (Lisboa, 2022)(Folha, 2023) between the systems of power and Indigenous Peoples in Brazil.

The Ministry of Indigenous Peoples includes Indigenous lawyers, Indigenous social workers, Indigenous anthropologists and many Indigenous professionals that have been actively involved with their causes for a long time. Lack of representation has now been significantly reduced as more Indigenous people have access to education and positions that give them the long-needed participation in the debate about their lives.

Four indigenous women were elected to the Chamber of Deputies in 2022: Sônia Guajajara, Célia Xakriabá, Silvia Waiãpi, and Juliana Cardoso. They took over as federal deputies on February 1, 2023, on the day of the start of the new Legislature of the National Congress.

Xakriabá has a Master’s in Sustainable Development and is post-graduated in Anthropology. Célia is one of the founders of the National Articulation of Indigenous Women Warriors of Ancestry. As a Minas Gerais Department of Education member, she collaborated to open indigenous schools and quilombolas and reopen country schools throughout the state.

The active participation of Indigenous people in the Legislative, Executive, Judiciary Powers and Academia is crucial for changes to happen and will most certainly be constantly challenged.

Governmental organizations, working with representatives of the Minister, reported the death of more than five hundred and seventy (570) Yanomami children in the last four years after Jair Bolsonaro authorized miners to enter indigenous land. Thirty Yanomami girls under sixteen are pregnant by miners and other invaders. (Business & Human Rights Centre, 2023).

On January 20, 2023, the federal government declared a public health emergency in Brazil’s largest Indigenous Reserve. (Gozzi, 2023). On January 31, 2023, the Brazilian Army, Navy, and Air Force were sent to expel land invaders, protect the Yanomami people from their attacks and rescue thousands of sick and dying Yanomami people who were the object of continuous violence in their land. (Philips, 2023)

In the country with the highest Catholic population, colonized by the Portuguese, the Doctrine of Discovery, its manifestations and effects remain ignored by the majority.

Papal Bull Dum Diversas (1452) was issued eight years before the arrival of the Portuguese on the coast of Brazil. It called for non-Christian peoples to be invaded, captured, vanquished, subdued and reduced to perpetual slavery. As a follow-up, in 1455, the papal bull Romanus Pontifex was issued to protect the King of Portugal’s ascendancy over new lands discovered, forbidding other Christian kings from infringing Portugal’s King’s practice of trade and incursions of colonization in specific regions. (Slaterry, 2005).

Even as the Yanomami tragedy is in the news everywhere, references to the existence of the Doctrine, its Impact on Indigenous people, the environment, or any respect to how it shapes the Brazilian landscape today are nonexistent.

There is, nevertheless, a piece of Art that deserves special attention as it has been telling the History of the Doctrine in Brazil since 1860.

The 1860 oil on canvas by famous artist Victor Meirelles, currently on display at Museu Nacional de Belas Artes in São Paulo, Brazil, tells a chapter of the Doctrine that is hidden at first glance.

‘First Mass in Brazil’ by Victor Meirelles (1860) - Museu Nacional de Belas Artes, SP, Brazil.

The painting ‘The First Mass in Brazil’ gives an accurate visual account of the rituals of the Doctrine, constituting a well-documented starting point to shed light on the Doctrine’s principles and its powerful presence since the initial colonial days when the Portuguese arrived in the coast of what is now Brazil.

Historian studies are not free from ideology. While setting forth the past, putting together bits and pieces, they cannot guarantee that what remains is the most important, the most representative part of the event, concluded Gottschalk (Gottschalk, 1979).

The same applies when artists use the powers of Art to represent Historical events.

Beginning with the painting’s title, “The First Mass in Brazil”, we meet the incomplete, if not deceiving, “bit of History” that demands attention.

Painted by Victor Meirelles in Paris in 1859-1861, the almost 14.9 square inches (9,6 square meters) piece became one of Brazil’s most well-known canvases. Its presence is a must in any pedagogical publication.

Meirelles was influenced by Horace Vernet’s painting ‘First Mass in Kabylie’. Vernet was an eyewitness to the Catholic Mass celebrating French colonization in North Africa, and his legitimacy as a historical painter inspired the Brazilian painter (Castro, 2009).

In April 1500, Pedro Álvares Cabral’s fleet landed in what is now known as Brazil. In the fleet was Pero Vaz de Caminha, a Portuguese civil servant. Caminha officially described the ceremony of the two Catholic masses celebrated in the new land.

He wrote a detailed letter to the Portuguese King, as expected from a knight in his position. The original letter is in the National Archive of The Tower of Tombo, Lisbon (Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo, Lisboa, in Portuguese). It is frequently mentioned in Brazilian History books as a testimony of the Portuguese’s benevolent encounter with the land’s inhabitants.

Due to the secrecy with which the Kingdom of Portugal has always involved reports of its discoveries, the entire content of Caminha’s letter was made public only in the nineteenth century by Father Manuel Aires de Casal in his ‘Corografia Brasílica’ in 1817. (Lencione, 2009)(de Casal, 1817). Only then could the context of the elements of the painting be fully understood.

The painting, Meirelles said, followed the description contained in Caminha’s letter.

In reality, the painting gives an accurate image of the Portuguese adopted ritual of possession, with all the Doctrine’s required steps and components.

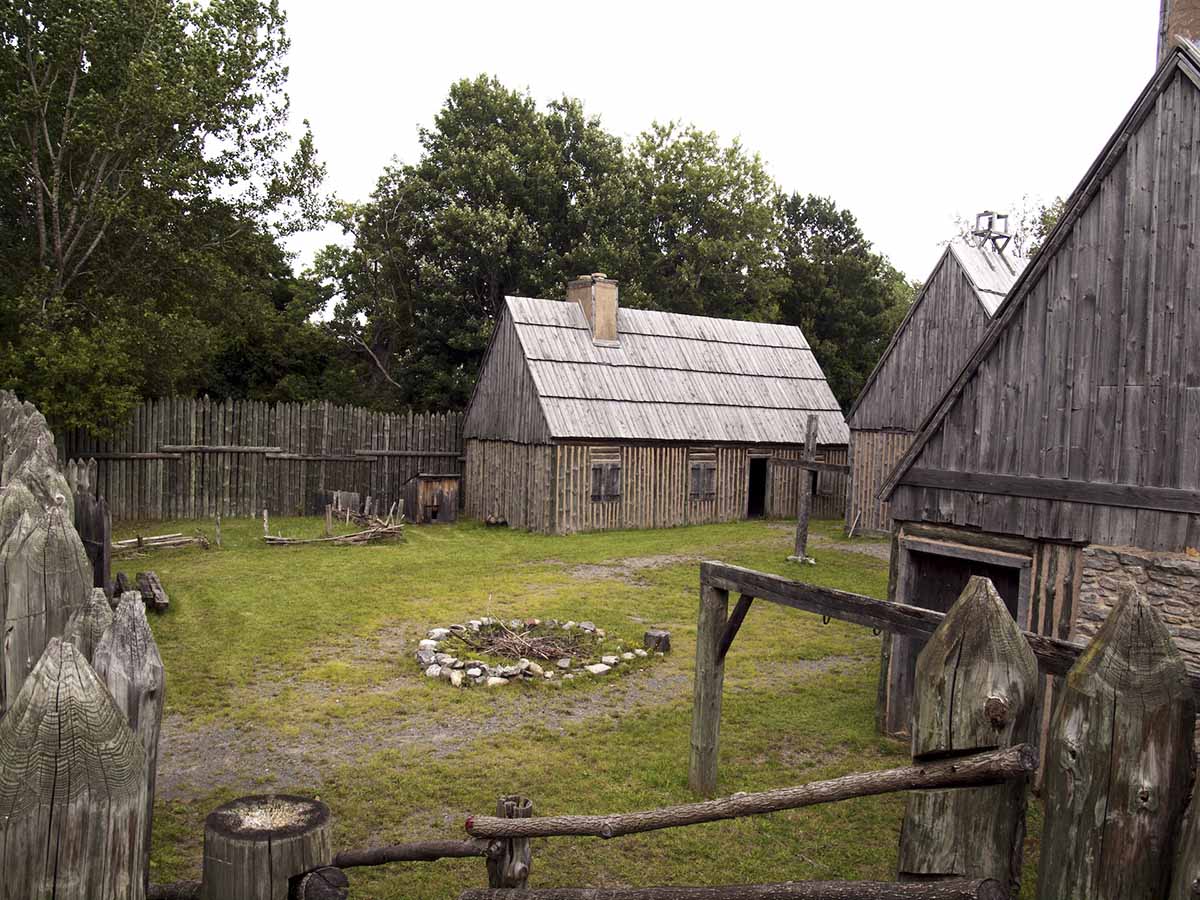

The Portuguese used to record their navigation discoveries by planting tall stone pillars topped by a square stone where they carved the year of the expedition, the name of the leader of the expedition and the name of the Portuguese King. On top of the carved square stone was a cross. (Seed, 1995, p.132).

The ritual of possession and enacting authority over discoveries also required detailed written documentation. Caminha’s letter to the King fulfilled this requirement (Seed, 1995, p.180).

Like Horace Vernet’s painting, Meirelles’ painting documents the colonization ritual. Like Vernet, Meirelles named the possession ceremony “The First Mass in Brazil”.

As we observe the oil on canvas, the image focuses on the left, where a central religious man performs the ritual while other religious men witness it. These figures occupy a higher level except for two men in armour on the left. Some indigenous people observe or find protection on top of a tree on the right.

In a distant circle, observing the events, are indigenous people depicted with a wide range of expressions: fear, anger, astonishment, and incredulity. A baby being breastfed, scared children, warriors, and young and old indigenous populate the left side of the painting. Many indigenous are distant, some with brawling arms, some pointing at the ships in the sea. There is a subtle sense of chaos among them.

In the background, the landscape is made of trees with large canopies, mountains, and a blue sky. The ocean and glances of ships of the Portuguese fleet are represented in the right corner, and all constitute a detailed visual representation of what was described in Caminha’s letter to the King.

After the Doctrine’s rituals or acts of possession were executed, Portugal’s legal claim was established. (Seed, 1995)

Consequently, these Indigenous people portrayed in the painting, inhabitants of that land for more than two thousand years, became Portuguese possessions.

After Cabral’s discovery in 1500, the focus of the Portuguese Crown in its colony was the extraction of resources from the land, such as brazilwood, precious minerals and whatever could be found.

Signed between Spain and Portugal, Tordesillas Treaty created a line of demarcation, allocating the land to the east of the line to Portugal and the land to the left of the line to Spain.

The effects of the 1494 Treaty remain embedded in the Brazilian system of laws and treaties that reinforce the Yanomami’s exploitation as their land is repetitively invaded, and they are victimized by the same kind of violence that existed upon the arrival of the Portuguese.

In 1530, soon after the “discovery” and following the demarcation by the Tordesillas Treaty, the territory of what became known as Brazil was divided into fourteen strips of land and granted to nobles of trust of King D. João III (1502-1557). The land, called hereditary captaincies, could then be passed from father to son.

The legacy of hereditary captaincies is present today through the concentration of land ownership and perpetuation of Brazilian ‘colonelism’ that maintains power in many areas as the same families control states and create difficulties in demarcating indigenous land.

Meirelles’ painting gives a sense of the Portuguese arrival in indigenous land. Papal bulls issued by Pope Nicholas in 1452 and 1455 provided the right to take possession of indigenous peoples’ land and goods “to convert them to you, and your use, and your successors the Kings of Portugal” (Slattery, 2005).

Meirelles’ painting is present in most Brazilian schoolbooks. On the other hand, absent in Brazilian education, the Doctrine of Discovery is part of History that is still “hidden in plain site”.

Informed knowledge of the origins of today’s catastrophic events passes through awareness and information about the principles and methods included in the Doctrine of Discovery.

Racist elements of the Doctrine are frequently part of the discourse of some Brazilian politicians and authorities.

Recently, while defending his policy of opening indigenous land to miners, loggers and agribusiness, Jair Bolsonaro, president of Brazil until January 1, 2023, declared:

“The Indian has changed; it is evolving. Increasingly, the Indian is becoming a human being equal to us”.

(Jair Bolsonaro, Presidential live, January 24, 2020)

On August 16, 1998, the same Jair Bolsonaro declared, in a speech in the Brazilian House of Commons:

“The Brazilian cavalry was very incompetent. Competent, yes, was the North American cavalry, and it decimated the Indians in the past and nowadays have no such problems in their country.”

As agribusiness pushed for limitations in the demarcation of indigenous land, presidential support by Jair Bolsonaro was necessary to approve the so-called ‘Time Frame’ (“Marco Temporal”, in Portuguese).

“Marco Temporal” is a legal thesis constructed jurisprudentially in which the Doctrine’s principles are present in all its colours. The case of the land known as ‘Raposa Serra do Sol’ was discussed in Brazil’s Supreme Federal Court (STF) in 2009. In it, the Supreme Court decided that the article of the Constitution that guarantees the enjoyment of the lands traditionally occupied by the Brazilian indigenous should be interpreted by counting only the lands in possession on October 5, 1988, the date of the promulgation of the 1988 Brazilian Constitution. Such an interpretation would validate the acts of the Brazilian military dictatorship when indigenous people were frequently murdered and expelled from their land.

As the Yanomami’s catastrophe unfolds, Brazil is still debating on two fronts whether it is legal or not to determine a time frame for the demarcation of indigenous lands. The discussion takes place on two legal fronts: it is to be voted on by the Supreme Court (STF), and there is an attempt to approve Bill 490/2007. Such Bill 490/2007 includes extremely problematic provisions, impeding Indigenous people from claiming additional land to expand already demarcated territories. It also allows the government to eliminate Indigenous reserves threatening Indigenous people’s livelihood and cultural survival. Bill 490/2007, if approved, embeds overbroad terms that could lead to forced removals of indigenous peoples from their land, as stated by Human Rights Watch. The principles evoked are not by coincidence similar, if not equal, to those included in the Doctrine of Discovery. It expands government powers allowing it to invade the land and contact even Indigenous peoples living in voluntary isolation.

Furthermore, as the papal bulls, the bill gives the government the power to explore, at its own will, energy resources, set up military bases, and expand strategic roads in Indigenous lands without any consultation with Indigenous peoples.

The principles of the Doctrine and its manifestations, although hidden under layers of misinformation and omission, are, hidden in plain sight, embedded in Bills like Bill 490/2007.

Regardless of the Catholic Church’s discourse about protecting the environment and calling for the preservation of the forest, there are no words about its role in enacting those bulls, let alone about refusing to reject the Doctrine. Amid the scandalous news, modest donations by the Catholic Church have been offered, and neither compensation nor emancipation is provided to the original people victimized by their papal bulls.

In 2007, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) was ratified by all its participants except for four countries: Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the United States. Information about the Doctrine is continuously being spread in those countries. Moreover, regardless of the inefficacy of the Canadian Senate passed Bill C-15, which seeks to align Canadian Law with UNDRIP but does not directly implement many of the declaration’s articles into Canadian Law, only partially rescinding the effects of the Doctrine of Discovery in Canadian Law, the Brazilian case, signatory of the 2007 UNDRIP, is even more oblivious to the damage caused by such Doctrine.

Regardless of Brazil’s ratification of the 2007 UNDRIP, it produced no practical effects, and the Brazilian government still needs to account for its lack of compliance.

Robert Miller’s work, “The Doctrine of Discovery: The international law of colonialism”, highlights the need to recognize and address the legacy of colonialism to ensure Indigenous sovereignty.

While Brazilian school books include themes such as occupation, consolidation of the Portuguese in America, discovery, colonization, and indigenous peoples, there is no reference to the Doctrine of Discovery in Brazilian publications in Portuguese, the country’s primary language.

In January 2023, the recently elected Brazilian Minister for Human Rights and Citizenship, a jurist and scholar, demanded the presence of federal policy in the Yanomami land to rid the land of criminals and to protect the lives of all that are under the gun of the miners and their bosses operating the economic mining cycle started by the Portuguese. In invaded land where 28,000 Yanomami live, there are 20,000 miners, and behind them, a powerful and wealthy network of mining companies and organized crime enriching and expanding with no accountability.

Hate crimes and genocide are never isolated events but result from hatred and violence incitement. The current extreme right-wing government has targeted the indigenous people and many other groups in Brazil in a dehumanizing discourse that seemed like a preparation for annihilating indigenous people without a reaction from the population.

Indigenous people in Brazil, among them the Yanomami, have been on the brink of genocide. While Canadian Indigenous people asked the pope to repel the Doctrine of discovery, Brazilian indigenous people remained oblivious to the role of the Doctrine of Discovery in their fate.

The invasion of the Yanomami’s land and the allegedly deliberate destruction of their ability to feed themselves, the contamination of the waters and the spread of disease are a repetition of manifestations of the Doctrine of Discovery, a topic totally out of sight in most of this prominent Catholic country.

Conclusion

The Doctrine of Discovery has had a long and devastating history in Brazil. From enslavement, exploitation and the denial of Indigenous sovereignty to the genocide of the Yanomami in the Amazon, this legacy continues today with the ongoing struggle for Indigenous rights.

Indigenous people have traditionally played the role of “guardians” of the Amazon, an immense natural territory vital in the fight against climate change. Indigenous Brazilian legislators, Indigenous Organizations, lawyers, judges and attorneys of justice are fighting back. However, a piece of the puzzle is still missing: the recognition that The Doctrine of Discovery has caused immense suffering and injustice to Indigenous peoples.

To create a more positive and equal future for all Brazilians, it is essential to recognize the truth of the country’s History and to eradicate the vestiges of the Doctrine of Discovery from Brazilian Law and society. It is time to bring down the veil of ignorance that hides the origins of ongoing violence against Indigenous people - papal bulls constituting the Doctrine of Discovery.

It is time to make common knowledge the fact that behind the Yanomami oppression and appropriation of land are the principles of the Doctrine. It is as if they always retained power over the region’s first inhabitants, even when the Doctrine remains hidden from common knowledge.

REFERENCES

-

Bell, J., Sterett, S., & Young, M. (2018). Editors’ Note. Law & Society Review, 52(3), 559.

-

Business & Human Rights Centre. (2023). “Complaints Indicate That 30 Yanomami Girls Are Pregnant, Victims of Abuses Committed by miners in Roraima”(in Portuguese: Denuncias Apontam Que 30 Meninas Yanomami Estão Grávidas, Vítimas de abusos Cometidos por garimpeiros em Roraima). Retrieved February 26, 2023, from https://www.business-humanrights.org/pt/%C3%BAltimas-not%C3%ADcias/brasil-denuncias-apontam-que-30-meninas-yanomami-est%C3%A3o-gr%C3%A1vidas-v%C3%ADtimas-de-abusos-cometidos-por-garimpeiros-em-roraima/

-

Castro, P. (2009). História da Historiografia. 0 (2): 29–49

-

Charny, I. W. (2000). Encyclopedia of genocide. ABC-CLIO.

-

COIAB, (2010).”Brazilian indigenous federation is key Conservancy ally in the Amazon rainforest”. Coordenação das Organizações Indígenas da Amazônia Brasileira. Retrieved February 26, 2023, from https://web.archive.org/web/20100317212302/http://www.nature.org/wherewework/ southamerica/brazil/work/art18068.html

-

Fricker, M. (2011). Epistemic injustice: Power and the ethics of knowing. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

-

Folha de São Paulo (2023). “No Government Has Ever Properly Addressed Land Issues in the Amazon”. Retrieved February 27, 2023, from https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/internacional/en/scienceandhealth/2023/02/no-government-has-ever-properly-addressed-land-issues-in-the-amazon.shtml

-

Hayner, P. (2010). “Unspeakable Truths: Transitional Justice and the Challenge of Truth Commissions.” (“Unspeakable Truths: Transitional Justice and the Challenge of Truth …”) Routledge. ISBN 978-0415806350.

-

Hemming, J. (1978). Red Gold: The conquest of the Brazilian Indians. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

-

*House of Representatives, Brazil. (2022). “House of Representatives will have four Indigenous Deputies.” **(in Portuguese: Câmara dos Deputados Terá quatro Deputadas Indígenas).) Retrieved February 26, 2023, from https://agenciabrasil.ebc.com.br/politica/noticia/2022-10/camara-dos-deputados-tera-quatro-deputadas-indigenas

-

ISA, I. (2022, April 11). Instituto Socioambiental - Yanomami Indigenous Land. Retrieved January 31, 2023, from https://www.yanomami30anos.org/en

-

Gottschalk, L. R. (1969). Understanding history: A primer of historical method.

-

Gozzi, L. (2023, January 24). Brazil airlifts starving Yanomami tribal people from the jungle. Retrieved January 30, 2023, from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-64381922

-

Indigenous Title and the Doctrine of Discovery - ictinc.ca. https://www.ictinc.ca/blog/indigenous-title-and-the-doctrine-of-discovery

-

Lencioni, S. (2009). Região e Geografia. São Paulo: EdUSP. ISBN 978-85-314-0515-0

-

de Casal, M. A. (1817). Corografia Brazilica ou Relação historico-geografica do Reino do Brazil. Régia Oficina Tipográfica.

-

Lisboa, J. (2022). Indigenous peoples and the judiciary in Brazil: an appeal for a legal anthropology approach. Vibrant: Virtual Brazilian Anthropology. 19. 10.1590/1809-43412022v19a803.

-

MENA Report, (2023). Brazil will take a resolution on the health of Indigenous peoples to the WHO.

-

Miller, R. (2015). The Doctrine of Discovery, manifest destiny, and American Indians. Retrieved February 19, 2023, from https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2689279

-

Miller, R. (2019). “The doctrine of discovery: The international law of colonialism.” Indigenous Peoples’ JL Culture & Resistance.https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3cj6w4mj

-

Miller, R., & D’Angelis, M. (2011). Brazil, Indigenous Peoples, and the International Law of Discovery. Retrieved February 26, 2023, from https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjil/vol37/iss1/1/

-

Philips, T. (2023). Jair Bolsonaro accused of acts of genocide against Amazonian Group. Retrieved March 11, 2023, from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/jan/22/lula-accuses-jair-bolsonaro-genocide-yanomami-indigenous-amazon

-

Philips, T. (2023). ‘A War Society Doesn’t See’: The Brazilian force driving out mining gangs from Indigenous Lands. Retrieved March 11, 2023, from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/feb/28/brazilian-force-driving-out-mining-gangs-indigenous-yanomami-territory-bolsonaro

-

Permanent forum for Indigenous peoples. (n.d.). Retrieved February 19, 2023, from https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/unpfii-sessions-2.html

-

Reuters. (2023, January 23). Evidence of ‘genocide’ among Brazil’s indigenous Yanomami, says Minister. Retrieved January 30, 2023, from: https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/evidence-genocide-among-brazils-indigenous-Yanomami-says-minister-2023-01-23/

-

Sassin, (2023, January 26). Yanomami genocide: Prospectors and authorities are investigated. Retrieved January 30, 2023, from https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/internacional/en/scienceandhealth/2023/01/yanomami-genocide-prospectors-and-authorities-are-investigated.shtml

-

Seed, P. (1995). Ceremonies of possession in Europe’s conquest of the New World: 1492-1640.Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press.

-

Livermore, H. V. (1976). A New History of Portugal (pp. 127–139). Cambridge University Press.

-

Thorpe, A. (2018). Pop-up property: Enacting ownership from San Francisco to Sydney. Retrieved February 19, 2023, from http://www5.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/UNSWLRS/2019/94.pdf

-

Walker, R.S., Kesler, D.C., & Hill, K.R. (2016). Are Isolated Indigenous Populations Headed toward Extinction? PLoS ONE, 11.

SUGGESTED CITATION

Telma Alencar, "Uncovering the Invisible: The Doctrine of Discovery, its Impact on the Brazilian Indigenous Peoples, on the environment and how it continues to shape the Brazilian landscape today: English," Doctrine of Discovery Project (3 April 2023), https://doctrineofdiscovery.org/blog/uncovering-invisible-en/.

Share on

Twitter Facebook LinkedInDonate today!

Open Access educational resources cost money to produce. Please join the growing number of people supporting The Doctrine of Discovery so we can sustain this work. Please give today.