Reappraising the Doctrine of Discovery

Again, were we to inquire by what law or authority you set up a claim [to our land], I answer, none! Your laws extend not into our country, nor ever did. You talk of the law of nature and the law of nations, and they are both against you. ~ Corn Tassel (Cherokee, 1785)

The European doctrine of discovery principle, recognized as recently as 1986 by a federal district court as “a legal fiction,” nevertheless remains one of the most entrenched and baffling legal doctrines undergirding federal Indian policy and law. It’s continuing legal and perceptual force perpetuates a second class national status for Native nations and relegates individual Natives to a second class citizenship status with regards to their incomplete property rights. This doctrine holds, under its most widely understood and debilitating definition, that European explorers’ ‘discovery’ of land in what became known as the Americas gave the discovering European nation–and the United States as successor–absolute legal title and ownership of land, reducing Indigenous peoples to being mere tenants holding only a lesser beneficial interest in their Aboriginal homelands.

Although this bizarre doctrine has come under increasing and well-deserved scrutiny by Indigenous and non-Indigenous scholars and commentators, the discovery principle, along with the doctrine of plenary power and the trust doctrine, represents one of the essential paradigmatic legs on which is constructed the federal government’s allegedly superior political and territorial standing vis-a-vis Indigenous nations. Like these other important and equally problematic legal rules, discovery has more than one definition. When it is defined as conquest or as benevolent paternalism, it belittles the autonomy of Native nations and leaves them in a relatively powerless political and economic position to the federal government. It deprives Native nations of full legal ownership of lands they have inhabited since time immemorial.

However, and to use Chief Justice John Marshall’s phrase, when we view the “actual state of things” that developed during the colonial and early American period, discovery was actually understood as doing nothing more than granting exclusive and preemptive rights to the discovering nation. And the exclusive right the U.S. gained was the right to be first purchaser of Indigenous land should a Native nation decide to sell any of its territory. It is this “actual state of affairs” that this essay recalls and elaborates on.

The Pope “Discovers” Discovery

Originally, the concept of “discovery” was a theological fiction first produced in the late 1400s by the Catholic Pope. It was later transformed into a political fiction by European heads of state, and then into a legal fiction by Chief Justice John Marshall in his first major Indian law case, Johnson v. McIntosh in 1823. In present-day parlance discovery has been dangerously re-purposed as popular fiction that serves to revise neo-colonial history, fuel oppressive legal decisions, and assuage majority culture guilt. Left unchallenged, the myth-making associated with the way discovery is currently defined–that it completely eradicated or at a minimum diluted Indigenous title–poses grave threats to Indigenous legal, political, and cultural identity because such definitions wrongly deny the inalienable sovereign rights of Native peoples to governance and full title to their own territories.

Without question the doctrine of discovery is one of the most important tenets of federal Indian law, working in tandem with other doctrines (e.g., trust, plenary power, reserved rights) that provide the ambiguous and uneven political framework for modern day Indigenous/State relationships. Notwithstanding its general acceptance, the discovery concept has been misused and misunderstood and serves to distort perceptions of both the past and present and it should be stricken from the federal government’s political and legal vocabulary.

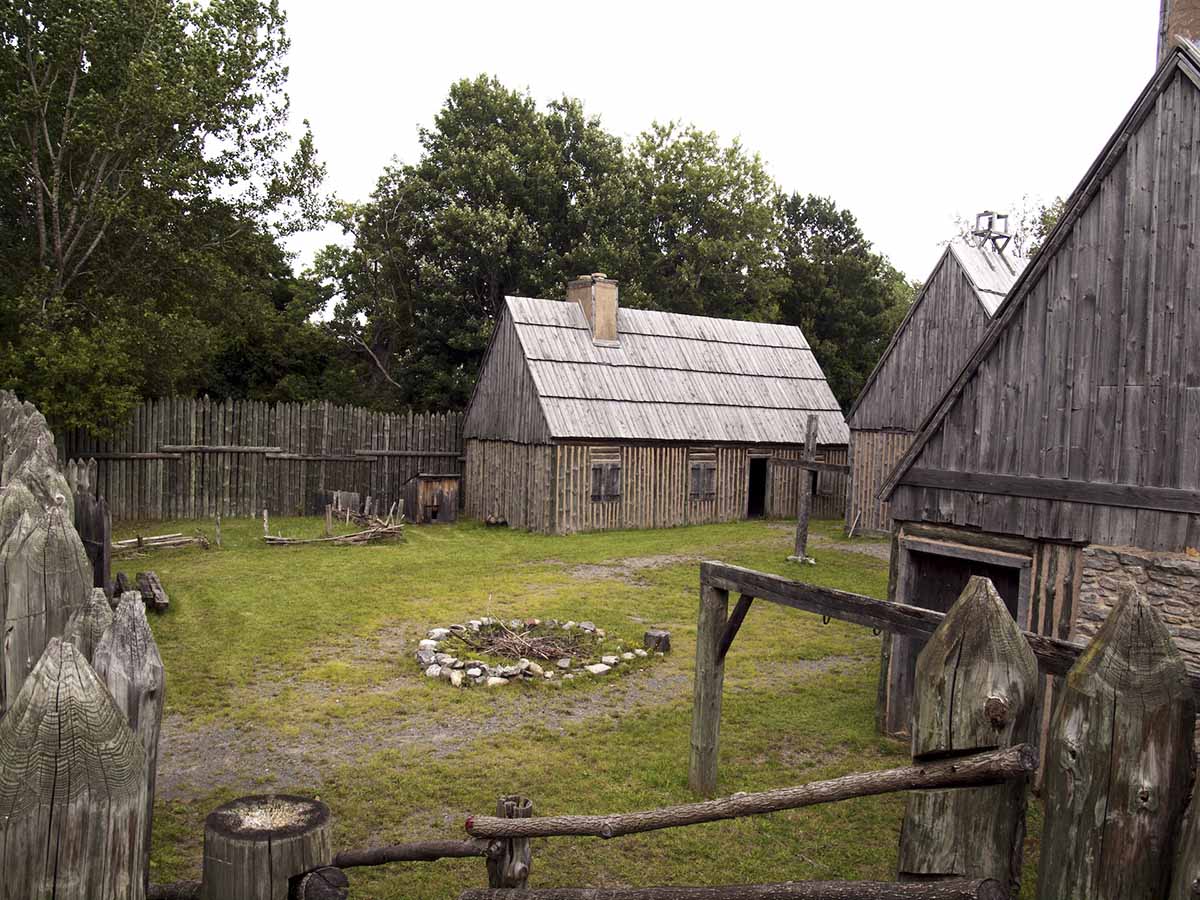

Discovery, as originally conceived in Pope Alexander VI’s 1493 papal bull, granted the Spanish exclusive interests in the Americas. When Portugal petitioned for a share of the spoils the following year the Treaty of Tordesillas granted both countries the authority to divide much of the Western hemisphere between them and to ignore the territorial rights of existing Native nations in the process. This sanctified division is what most people remember about the doctrine.

But it is more complicated than just saying the Pope gave European Catholics the rights to colonize and convert. In reality, the absolute denial of Native land rights was replaced less than fifty years later when Charles V, the devoutly religious Spanish emperor, sought the advice of Francisco de Vitoria, a prominent theologian, as to what rights the Spanish could legally and morally claim in the New World. Vitoria, in a clear rebuttal to the Pope and the discovery notion, declared that Natives peoples were the true owners of their lands. He reasoned the Spanish could not claim title through discovery because this action could only be justified where property was ownerless.

Felix Cohen, a leading architect of federal Indian law, reiterated Vitoria’s statement in his well-known Handbook of Federal Indian Law (1941), when he wrote that “even the Pope has no right to partition the property of the Indians, and in the absence of a just war, only the voluntary consent of the aborigines could justify the annexation of their territory.”

So, in fact, the original no-holds barred papal doctrine of the discovery was discarded early on in favor of Vitoria’s view of Indigenous property rights. Subsequent legal and political relations between Native nations and competing European powers over the following three centuries were generally based on this philosophical understanding of Natives as true landowners. Treaty-making between Indigenous nations and Europeans, and later the U.S, affirmed that Native peoples were recognized as land-owning nations on par with any other political power.

Had Pope Alexander’s original sweeping decree of unlimited Christian domination held sway, there would have been no reason for colonizers to engage in complex diplomatic relations with Native nations. Furthermore, contrary to common assumptions that ultimate legal title to occupied Native lands passed upon discovery to European states or the U.S. as successor, the historical record, both written and oral, shows that legal ownership remained with Tribal nations. And for the most part, Native peoples retained legal ownership of their respective territories until such time as they formally ceded their claims to lands in consensual treaty arrangements with one of the competing European states or, later, the American government.

The Confirmation of Indigenous Land Rights in Treaties, Laws, and Cases

Three classes of evidence—1) the actual political and diplomatic relations between Native nations and Spain, France, Great Britain; 2) the record of the federal government in its dealing with Native peoples as evidenced in treaties, policies, and statutes; and 3) a number of relevant Supreme Court decisions that have addressed the doctrine of discovery–affirm that ownership of the North American continent rested in the hands of Indigenous peoples.

This is not to say that massive injustices were not committed against Native peoples, with great swaths of land being taken without viable recourse. These events have been well chronicled. However, it is critically important that Native peoples recall their actual historical engagements with foreign powers and the over-arching legal basis of their inherent and recognized rights to land ownership. Even as other political powers sought to vanquish them, Native peoples retained power over their lands, just as they retained inherent political, economic, and cultural sovereignty. To simply say that the papal discovery doctrine allowed colonizers to take land without consideration of Indigenous property rights is to passively accept a revised history that wrongly claims that Native nations never had those rights in the first place.

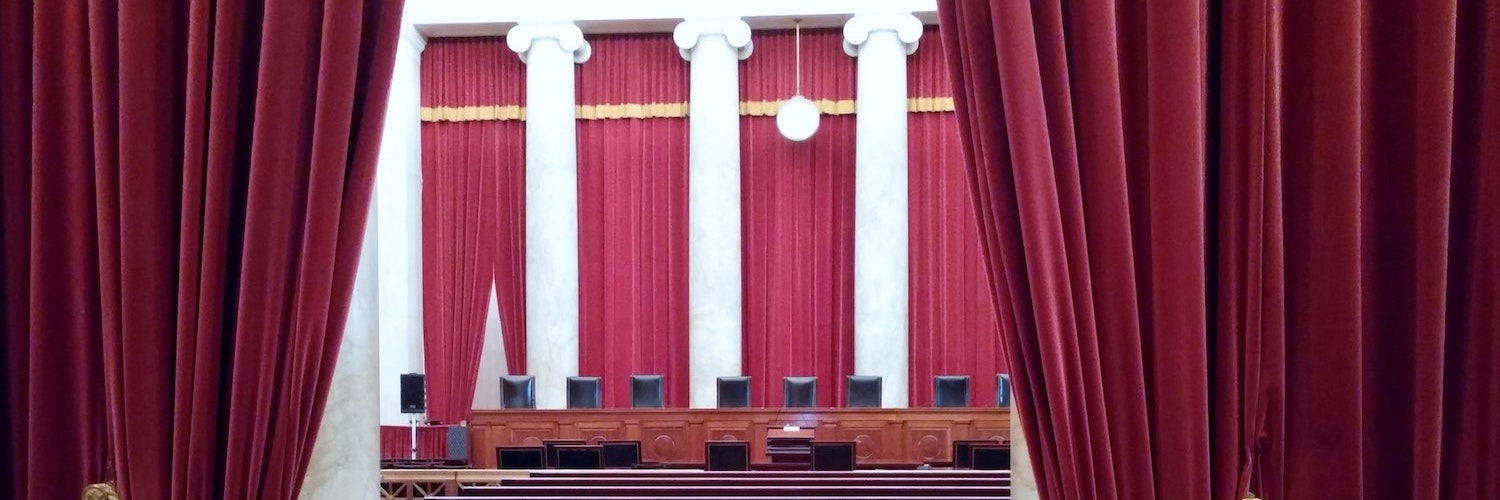

In reality, the discovery doctrine (either the papal or the Vitoria version) was only sometimes referenced during much of the colonial period as land was bought, sold, and traded with the understanding that Indigenous peoples held ownership rights. But it was famously reprised and redefined by the U.S. Supreme Court in Johnson v. McIntosh (1823) when Chief Justice John Marshall, in a case without any Native parties, dramatically modified historical understandings and suggested the doctrine of discovery was both a mechanism designed to prevent conflict between European competitors vying for lands in the New World and that it provided discovering powers with a “superior” title to the one held by Native peoples. However, he also declared that in relations between colonizing powers and Indigenous nations, the doctrine affirmed that Tribal nations were the “rightful occupants of the soil,” and acknowledged that they had “a legal as well as just claim to retain possession of it, and to use it according to their discretion.”

While on the surface, Marshall’s resurrection and redefinition of the concept offers some support for Indigenous property rights, the details of the decision were a major setback for Native peoples’ sovereign territorial rights. His interpretation gave the discovering state the exclusive or preemptive right to purchase land from the indigenous inhabitants. Even though Native nations had the right to own their lands, their right to sell was limited. In this sense, he wrote, “rights to complete sovereignty, as independent nations, were necessarily diminished.”

Marshall seemed fixated on the doctrine and reversed definitional course in Worcester v. Georgia (1832). Discovery he said, was merely “an exclusive principle which shut out the right of competition among those who had agreed to it; not one which could annul the previous rights of those [like tribes] who had not agreed to it.” The concept was thus reinvigorated and became a standard point of legal reference.

Since then numerous judicial rulings have referenced the doctrine. One of the most notable was Tee-Hit-Ton v. United States (1955) involving Alaskan Natives in which the Supreme Court equated the discovery doctrine with the doctrine of conquest. In that case, written during the destructive Termination era, the discovery doctrine was misused to deny Alaskan Native nations any legal title to their lands, whatsoever. Justice Stanley F. Reed’s inaccurate description of the Americans’ alleged conquest of Natives bears repetition: “Every American schoolboy knows that the savage tribes of this continent were deprived of their ancestral range by force and that, even when the Indians ceded millions of acres by treaty in return for blankets, food and trinkets, it was not a sale but the conquerors’ will that deprived them of their land.”

Reed’s statement ranks among the most glaring and racist misrepresentations of fact ever uttered by a Supreme Court justice. Little in the historical record corroborates his contention that Alaskan Natives or many other Native peoples had been conquered, and, in fact, federal Indian policy and the history of treaty making give ample evidence to the contrary.

Nevertheless, this spurious decision has never been overturned and it continues to undermine Indigenous property rights, as evidence by its citation in a recent 9th Circuit Court of Appeals decision, White v. University of California (August 2014), involving human remains of the Kumeyaay Nation of California.

Despite historical facts, the legal fiction of the discovery doctrine endures. But why is there such a drive these days to revert to the long ago discredited papal version of the doctrine of discovery when historical reality and ample legal evidence clearly show it was not used in any practical way by subsequent colonizers after Vitoria’s writings? Adherence to this discredited definition serves two purposes, both detrimental to contemporary Indigenous nations.

The first seems to be a well-intentioned eagerness by some, often with progressive Christian affiliations, to acknowledge the injustice of former generations of colonizers. By hearkening back to a time when immigrants to the Americas were given supposedly given free reign to conquer and pillage, today’s sympathetic non-Native citizens and certain church leaders of the larger culture can apologize for the sins of their forbears. At the same time, the exercise provides the opportunity for them to distance themselves from blame, even though most are the inheritors of privileges gained at the expense of Native peoples.

Second, as the mythical narrative goes, because the injustices were so numerous, so horrific and undocumented, there is a perception that no practical recourse remains. Conveniently, if there is no record, there can be no remedy so it’s time everyone agrees to heal, join hands, and move forward as one nation, putting grievances and claims aside. The phenomenon is fascinating—it is simultaneously an enthusiastic embrace of a historically inaccurate and cutthroat view of the discovery doctrine and a profound disavowment of current reality. In this way, overlaying history with the original papal doctrine of discovery becomes at once a way to show sympathy with Native peoples while at the same time denying them any substantive justice.

To simplistically explain away loss of territory as the fault of the doctrine of discovery is to ignore Indigenous retained land rights and forget that Native ancestors were determined, intelligent, and politically astute people who defended their sovereign territories through strength and reason. To accept a dumbed-down version of history is to relegate Indigenous people to the role of perpetual victim. It is to accept that Natives were “conquered” and as such are no more than rapidly disappearing ethnic groups of a by-gone era who no longer deserve the vital rights outlined in their diplomatic accords.

Words matter. Native peoples have come together to successfully challenge the use of derogatory mascots, to rename offensive places, and are presently fighting to retain the essential right to decide their children’s future, because it is plain that reckless use of words impacts Native peoples directly. While arcane legal terms may seem far removed from our daily lives, they also drive behavior and determine policy with significant consequences.

Abandonment of the flawed concept of the doctrine of discovery, both in legal and everyday parlance, makes good common sense. Indigenous nations should strive to enlist terms that accurately reflect what “actually” transpired in countless treaty negotiations, land transactions, and other binding agreements. To do so would be a significant first step in reformulating federal Indian policy and law so that justice, fairness, and historical accuracy were the basis of political relations.

SUGGESTED CITATION

David E. Wilkins, Ph.D. (Lumbee Nation), "Reappraising the Doctrine of Discovery," Doctrine of Discovery Project (15 February 2023), https://doctrineofdiscovery.org/blog/reapprasing-the-doctrine-discovery/.

Share on

Twitter Facebook LinkedInDonate today!

Open Access educational resources cost money to produce. Please join the growing number of people supporting The Doctrine of Discovery so we can sustain this work. Please give today.