Oak Flats and the Doctrine of Discovery unprecedented challenge and opportunity

Abstract

The case against Resolution Copper’s proposed mine in Oak Flat is an unprecedented opportunity for reckoning with the American ideal of religious freedom. This value was enshrined since its inception as one of the most basic tenets of human existence in American society. Freedom—religious freedom in particular—is perhaps the most important value that defines the United States. Yet this freedom was never meant for Indigenous nations, and in fact during the conquest of what has become the United States, Native peoples across the entire continent were systematically denied any right to or even ability to practice their spiritualities/belief systems. This is a reality which author Steve Talbot goes so far as to call spiritual genocide. This paper explores this ideal in the context of Resolution Copper’s mining project which threatens Oak Flat in Arizona. Oak Flat is sacred land for the Apache people, and the mine endangers not just the ecosystem, but the entire Apache nation. These pages trace the origins of the current reality in Oak Flat to the Christian Doctrine of Discovery. Oak Flat is an unprecedented court case that calls out the hypocrisy of the United States’ legal (and moral) foundations of universal religious freedom, which was never universal at all. Given this is such a central principle for US culture and identity, the implications and possible outcomes of Apache Stronghold v United States are of tremendous import—not just for the Apache nation, but for the entire United States.

Introduction

Oak Flat (Chi’chil Biłdagoteel), about 40 miles east of Phoenix, Arizona in the Tonto National Forest, is holy ground for the Apache people. It is a sacred site of communion for Apache tribes like the San Carlos and Chiricahua, whose ancestors are still very much alive, present, and communicative on this land. As Apache youth leader Naelyn Pike says, they “died for us to be here…to have a future.”1 But it is so much more than a mere site of cultural and religious significance for Indigenous. This land is the very source of the Apache’s being as a nation and as a people. It is their place of becoming, of rooting, of belonging in the Spirit. It is here that “God touched the earth.”2 Oak Flat is not just special for the Apache. It is the Apache people.

The land is currently under threat by the largest proposed copper mine project in North America. Chi’chil Biłdagoteel sits atop 40 billion pounds of copper, one of the largest untapped reserves on the planet. Resolution Copper—owned by two of the world’s largest energy powerhouses, Rio Tinto and BHP, Broken Hill Proprietary Ltd—claim that accessing these reserves is critical to keeping up with the growing global demand for copper products. Mining Oak Flat, they say, would provide up to a quarter of the United States’ demand through the next four decades3. It would create over 3500 local jobs, bringing $61 billion dollars into the local Arizona economy over its 60-year operational lifespan4. The remaining 75% of the extracted minerals would be exported to China and Taiwan. China, in fact—not the United States—is “positioned to be the chief beneficiary of the copper and other materials removed from the [Oak Flat] mine.”5

The mine would cause Oak Flat to collapse. The new technique used by Resolution Copper (an innovative but little-tested method called block cave or panel cave mining) would, once the copper reserves are depleted, leave nothing but a massive sinkhole in the land. With block cave mining, the minerals would be tunneled out of the area to a holding site nearby, where they would be crushed and then exported for processing. The mine tunnels, some over 7000 feet deep, would then cave in, and the sacred site of the Apache would become a massive depression in the desert over 1000 feet deep (slightly more than the Empire State Building is tall) and up to two miles wide. Oak Flat would become one of the largest open pits in the world.6

That is not the only danger by far. Toxic wastewater and contaminated mine waste would also leech into the surrounding waterways and aquifers. These waters are essential pathways of life for the Apache and for nearby Arizona communities like Globe, Miami, and Superior. The mine would not only sinkhole the entire sacred site of the Apache and surrounding Indigenous nations; it would make the entire area unsafe to visit.7 There is also the heightened concern that the contaminated water would reach Phoenix and Tucson, affecting millions in these larger urban areas. This pollution would have devastating consequences, with unknown long-term ecological and economic effects. These are well-known risks, despite Resolution Copper’s own claims that block cave mining is much safer and less environmentally invasive—and despite their repeated claims that water quality and availability would not be significantly affected.

Apache leader and founder of the Apache Stronghold, Wendsler Nosie Sr, likens the devastation to the destruction of Mt Sinai. It is Holy Ground, and its loss would mean much more than just catastrophic harm to the environment. Says Chairman Rambler: “The real cost of this bill is…desecration and destruction of one of our most important sacred sites.”8 This fight to save not just the land, but the spiritual and sacred connection to land—to who Apache people are—is at the core of the Stronghold’s case. The case, now in front of the 9th Circuit Supreme Court, is fundamentally a contestation of the hypocrisy of the American ideal of religious freedom and protections (which has historically not applied to Indigenous people). Apache Stronghold v. the United States is a matter of human spirituality and dignity on an unprecedented scale, with significance for us all.

Religious Freedom for (not) all

The right to free expression of Native beliefs is technically protected by federal acts of Congress, such as the 1978 American Indian Religious Freedom Act (AIRFA), and the 1993 Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA). The AIRFA “affirm[s] religious freedom for…Native nations”9, and the RFRA reinforces this. United States law formally guarantees religious liberty for Native Americans. Treaties like the 1852 Santa Fe agreement with the Apache are further promises that the United States would protect their land in perpetuity, and “secure the permanent prosperity and happiness”10 of the Apache people.

Freedom of religion and religious expression is likewise codified in American law, in the First Amendment of the United States Constitution. This freedom is considered the premiere founding value of American democracy, both the starting point and the peak principle for a healthy, coherent society. Clearly articulated in the Constitution, it seems to exclude no one. “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances (for the violation of such).”11

The impartiality and universality of the First Amendment seems to be an established fact. Since the very beginning, these guarantees of freedom have been the absolute defining characteristic of America. Freedom is synonymous with being American and belonging to this country. As generations of young Americans were told in history lessons, freedom—and religious freedom in particular—is the principal reason this country was founded. As the common narrative goes, the first settlers were on a journey away from religious persecution and ultimate prohibition of their faiths by tyrants in Europe. From day one, the United States united around this fundamental right to express both personal and religious beliefs.

This freedom was understood, and then written into United States law, as a matter of basic human dignity—so central to American society that it is hard to overstate the importance. It is not a stretch to say that without this essential liberty, the human cannot be fully human. In other words, there is no human being without this first, most basic of rights to express one’s spiritual beliefs. The human person does not exist without access to or a way of expressing their spirituality.

Yet for all its universality, this law has never applied to Native people. From before the time these words became law, Indigenous peoples have been excluded from this basic freedom. They have been stripped of this right and purposefully, systematically, even physically denied the right to practice their beliefs. This was done throughout early United States history through practices like boarding schools (meant to erase Native identity and culture); banning Native languages; banning Native religious practices, ceremonies and traditions; physical and psychological abuse; and the practices in Christian missions of forcing Natives to adopt their religions and assimilate into broader white society. This was all designed to “eradicate all signs of Indianness,”12 in the effort—as Commissioner of Indian Affairs wrote in 1882—to “reclaim them from barbarism, idolatry, and [the] savage life.”13

This eradication of Indigeneity began well before the Founding Fathers began writing the Constitution. It can be traced back to a series of papal bulls written by multiple Catholic popes in the 1400s, called the Christian Doctrine of Discovery. The Doctrine of Discovery justified, even mandated, both slavery and the conquest of the Americas in the name of God. These letters granted the Portuguese and Spanish kings at the time the right to “invade, capture, vanquish, and subdue” all “barbarous nations” that their explorers encountered on their kings’ missions to expand throughout the world.

The discovered lands, popes like Nicholas V reasoned in Dum Diversas, in 1452, were inhabited by pagans and infidels. These were “savages,” enemies of Christ who “had no right to an original, free, and independent existence.” The entirety of the Americas was thus deemed as terra nullius: null land (literally translated, land of the heathen or unbaptized person). It was a land of non-people. the territories of “Saracens, pagans, and other enemies of Christ” also included Africa. After invasion of these lands, Pope Nicholas V made it clear what to do: the “claimed right of domination was to…reduce their persons to perpetual slavery and to take away all their possessions and their property.” (Dum Diversas, 1452). This left little question about the intention and purpose of Christianity’s expansion of the new continent.

The pope’s documents of heavenly ordained domination opened up the Americas to the taking by Christian settlers. As per the Doctrine of Discovery, God was on the Christian expansionists’ side. As Pope Alexander VI wrote in one of these bulls, Inter Caetera, in 1493, it is He who entrusted the Europeans to go forth: “for we trust in Him, from whom all empires and dominations and all good things proceed.” This is the genesis of what become known in the United States as Manifest Destiny, and the interconnected belief in American exceptionalism. Conquer, capture, and ever onwards for more—it is God after all who tells us to do so.

Of course, the Doctrine of Discovery didn’t originate out of thin air—Pope Nicholas V, Alexander VI and others promulgated a divinely dictated dogma of non-civilized subhumanity, which justified conquest, conversion, control, and erasure—but their documents had centuries of germination. Their doctrines can be traced to the era of early Greek philosophy. Well-known theologian Luis Rivera14 connects the papal documents’ language and worldview to that of Greco-Roman thinkers several millennia ago, such as Aristotle, Plato, and Socrates. These intellects revolutionized early Western thought by articulating a clear hierarchy of civility and world order. In their very structured worldview, humans existed on distinct levels of perfection, as on rungs of a ladder. Barbarians simply did not have the kind of cultural rationality of more civilized nations. They were lower on the ladder and participated to a much lesser degree in the perfection of God. These people were, the philosophers mused, simply not quite people.

As the Christian world later developed, the dominant Western theology remained enormously influenced by these Aristotelian and Greco-Roman philosophers. In particular, the dichotomy of barbarianism versus civility entrenched itself as a well-established cultural worldview. It then became official doctrine with the papal teachings of divinely ordained domination. The perspective then spread around the globe as Christian missionaries and settlers did their worldwide work of invading, capturing, vanquishing and subduing. It became the de facto justification for conquering, marauding, and laying waste to entire populations of Native peoples. “Savages” simply belonged to a lesser order of being, and therefore did not count for anything. There was no wrong in this line of work. In fact, and at the heart of it all, as the popes made quite clear, those who did not subdue and conquer the enemies of Christ were the sinners (Dum Diversas).

By the time the United States was being settled, this view of conquest of the savage subhuman Other was so deeply rooted that it entered unquestioned into the constitution of the young country. The landmark 1823 case Johnson v. M’Intosh established the legal foundations for US federal Indian law—and cemented the Doctrine of Discovery in the American legal system. Chief Justice John Marshall’s ruling explicitly named the “right of acquisition,” or the law of nations. This was, he wrote, a principal established by the governing powers and “agreed upon**among themselves” (read, without any outside consultation). According to this pre-agreed contract without any outside consultation, Native Americans “had the right to occupy by the land, but no [right to] full sovereignty.”14 In other words, the powers at be created the game, and the rules, exactly as they wanted them—and were free to change them as they pleased. As per Johnson v. M’Intosh, the “fierce savages” may henceforth have protections and recognition, but no control; this meant land, but no real ownership. The land was taken; the conquered had lost.

Antipathy towards Indigenous peoples had been in American consciousness long before Chief Justice John Marshall’s decision. However, in the fevered decades of Manifest Destiny, numerous policies and decisions continued to invoke the Doctrine of Discovery as legitimation for the conquest of the West and the attempted extermination of the Natives. The examples are far too numerous—and their consequences too brutal—to detail here with sufficient consideration. However, the legal fever caught on so quickly that in 1835, just one decade after Johnson v M’Intosh, Judge John Catron was already declaring of the supremacy of the law of nations as a time-tested, universal truth. In State v Foreman (the Supreme Court of Tennessee), he upheld the governing powers’ ultimate sovereignty and declared:

the principle declared in 15th century as the law of Christendom that discovery gave title to assert sovereignty over and to govern the unconverted has been recognized as part of the national law. The law of nations [has stood] for nearly four centuries and…is now recognized by every Christian power in its political and judicial department…

Today: Making Connections

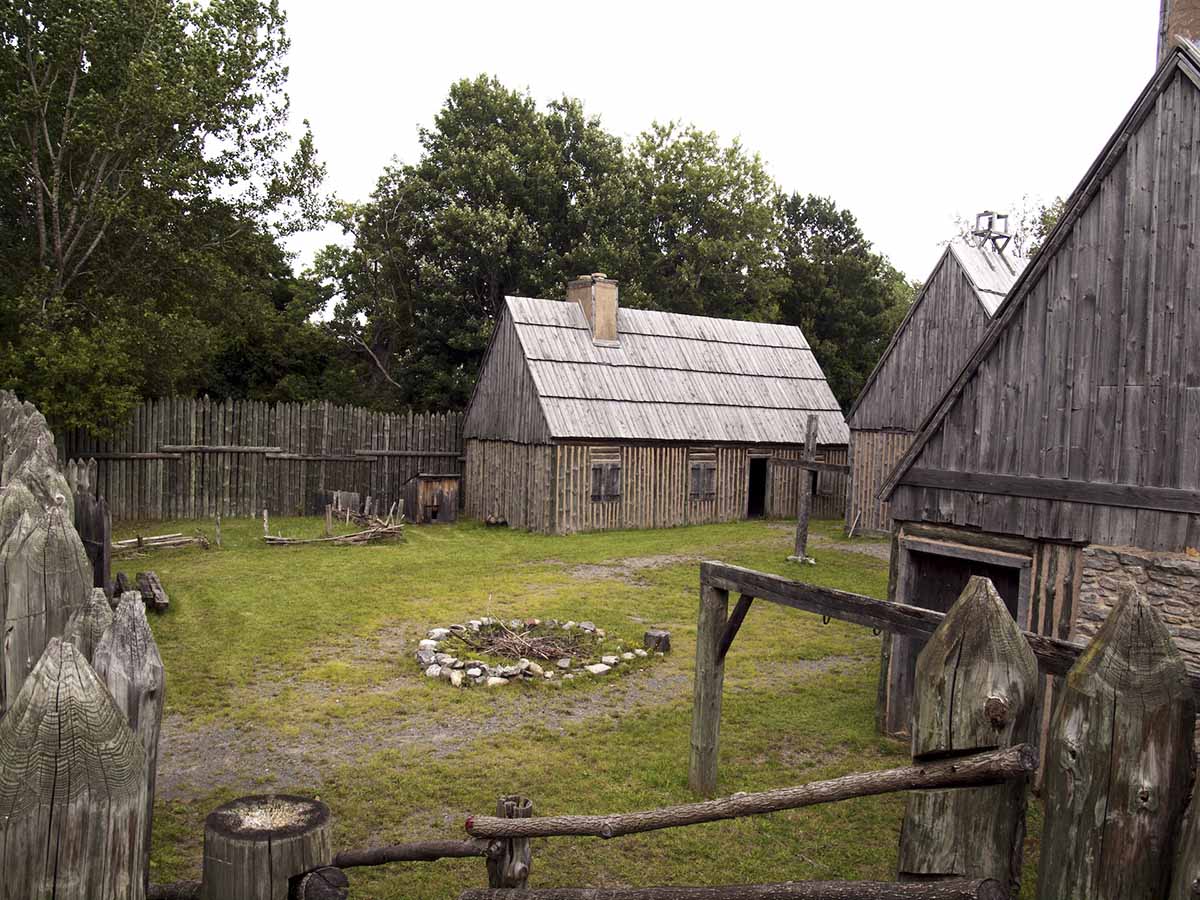

In 1872, the federal government created the San Carlos Reservation as a “‘tract of country…withheld from sale and set apart’ for the Apache.”15 This included much of the present-day Tonto National Forest and Oak Flat. Scholars, the Apache Stronghold, and Stronghold lawyers and supporters are clear: the very definition of the reservation in the first place “shows the Doctrine of Discovery at work.”16 As d’Errico argues, the US invoked the law of nations by presuming to own the land and then making it available (or not) as the US government saw fit. The creation of Oak Flat and the original reservation itself clearly demonstrates the extent to which domination over Indigenous peoples was considered universal truth in American society. It was simply an unquestioned fact of existence for both lawmakers and most settler citizens. It was as foundational and elemental a truth as religious freedom. This domination was also what it meant to be American.

Flashing forward 200 years since Johnson v. M’Intosh, and the cultural and legal legacy of domination is clearly reflected in the decisions made today around the proposed Resolution Copper mine and the future of Oak Flat.

In 1955, the Eisenhower administration placed protections against the sale of public lands to private (corporate) interests. For decades, Oak Flats and the federally-overseen Tonto National Forest were safe from mining or other development. However, these protections disappeared literally overnight in 2014. Two Arizona senators added what is known as a midnight rider to the Defense Authorization Act of 2015, a “must-pass” bill being passed urgently through Congress at that time. The last-minute addendum, written in by senators John McCain and Jeff Flake, privatized Oak Flat and 2400 acres of the surrounding Tonto Forest, opening the land for sale and wiping out 60 years of safeguards against development. It essentially directed the government to allow for the immediate sale of Oak Flat.

Resolution Copper had been openly “coveting” the land since 2005.17 Multiple administrations had upheld the protections and rejected calls for development of this sacred land, but these protections originally granted by the government were annihilated through privatization by the very same government. (Perhaps not surprisingly, the two senators involved in this midnight rider had vested interest in this land transfer. John McCain received campaign contributions from Rio Tinto, and Jeff Flake was a well-known former Rio Tinto lobbyist.) The authorization of this land transfer did require an environmental impact statement to be completed beforehand—but also included provisions “stating that no matter what the EIS might report, the transfer of title will go through 60 days after completion of the…assessment.”18 In other words, the land would be destined for development no matter what.

According to Becket Law, advisors to the Apache Stronghold, the government’s completely autonomous decision to privatize Oak Flat means the Indian sacred sites are left without protections, religious or otherwise. The Indian Religious Freedom Act simply would not apply to privately owned land. This unilateral decision is in a bad faith violation of the 1852 Treaty of Santa Fe that guarantees protection19 of the land designated for the Apache, in perpetuity. It is a violation of the freedom of expression for Native religions. This violation of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act and the First Amendment clause of religious expression is the basis for the 2022 Stronghold’s lawsuit seeking an injunction to stop the land exchange20. It is also likely a violation of the provisions of the UN Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. It is a violation of human rights in at least two ways, as per D’Errico.

First is the Doctrine of Discovery’s direct influence on the government’s decisions. The UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples condemns the DOD and all “doctrines, policies, and practices based on or advocating superiority of peoples or individuals on the basis of national origin or racial, religious, ethnic, or cultural differences.” Second, as the Declaration makes clear, “States shall consult and cooperate in good faith with…Indigenous peoples concerned through their own representative institutions in order to obtain their free and informed consent prior to the approval of any project affecting their lands…territories or other resources…” This clause of free, prior, and informed consent was directly ignored and violated by the midnight addendum to the Defense Authorization Act. The US government did not “consult and cooperate in good faith” with the Apache but rather catered to the lobbyists and representatives of Rio Tinto. Given the land’s vital importance for the Apache as spiritual lifeblood,21 this can certainly be considered a spiritual resource, akin to a natural one as fundamental as water. Clearly, natural resources are not the only elements at stake.

Fate of Chi’chil Bildagoteel, Fate of us all

Today, a growing number of people are becoming aware of the myriad environmental injustices that Indigenous communities and other communities of color are forced to confront—and have been confronting for centuries, since the first years of Christian settler domination—because of the domination legacy. Thought the power of denial is still very strong in our broader, predominantly Christian culture, the long-standing, long-lasting, and ongoing injustices done directly at the hands of Christian leaders and faithful are becoming harder to ignore. The calls for truth-telling, transparency, and transformation are growing ever louder in many sectors of society. These are calls for reckoning with the injustices and hypocrisies at the heart of our democracy, which are coded into the founding documents and laws of this nation. These laws are based in a worldview which sees Indigenous people as non-people, as sub-humans, as not worthy of rights, protections, or the freedoms to express their fullest human selves. The laws, in essence, come from a worldview which disallows entire populations of people to be: to exist.

It could not be clearer from the actions of the government: Despite being the sacred source of Apache people’s identity—land as hallowed as a temple or a cathedral—Oak Flat is still regarded as terra nullus, good for nothing except exploitation, and it is the Doctrine of Discovery which allows for this to be okay. It is the culture of conquest which allows for Resolution Copper to successfully lobby and privatize hallowed ground for profit and exploitation.

Oak Flat is thus a critical moment for much more than just the fate of the San Carlos Apache and Chi’chil Biłdagoteel. Christians are faced with a gigantic moral reckoning. The legal system is obviously implicated as well, as is the broader culture that upholds a value system wherein entire peoples are denied their basic right to exist. Even non-Christian or non-religious people have a stake in this case. Spiritual or not, no one is left unaffected.

The First Amendment points to an intractable truth that is ultimately much bigger, broader, and deeper than anything that can be expressed in a law or through a human legal system. This is a truth which the Apache, and other Indigenous peoples, have known and have lived for time immemorial. Spiritual freedom and expression is more than a law to be affirmed by politicians or Founding Fathers. It is an existential reality, inseparable from and synonymous with being alive. Spiritual expression is a condition of life, and non-expression is death.

The case of Apache Stronghold v. United States—by challenging the ways the First Amendment right has been denied to entire groups of people—represents more than just a broken and violated law. It gets at the fundaments of what it means to be human—because when that is taken away…what are we left with? We are all spiritual beings, part of a web of life that is much larger than we know. As such, we are all implicated by the court decisions coming out of the California 9th Circuit Supreme Court. What happens to Oak Flat, happens to us all.

Currently, the Stronghold case resides in the 9th Circuit Court in California and is slated for an 11-judge panel to hear the appeal on March 20, 2023.

Footnotes

-

Naelyn Pike, Youth Organizer, 2020. Written Testimony to the House Natural Resources Subcommittee for Indigenous Peoples of the United States Oversight Hearing on “The Irreparable Environmental and Cultural Impacts of the Proposed Resolution Copper Mining Operation.” https://www.resolutionmineeis.us/sites/default/files/references/pike-2020.pdf ↩

-

Poor People’s Campaign. The Holy Places are Rumbling… https://www.poorpeoplescampaign.org/we-cry-power/wendsler-nosie/ ↩

-

Resolution Copper, 2022. Oak Flat Myths and facts. https://resolutioncopper.com/myth-and-facts/ ↩

-

Resolution Copper ↩

-

San Carlos Apache Tribe press release, 3 Dec 2012. Joint statement of the San Carlos Apache Tribe, Concerned Citizens and Retired Miners Coalition, and Arizona Mining Reform Coalition http://www.azminingreform.org/sites/default/files/docs/O.F.PR%20Newswire%20final%20statement%20with%20revision.pdf ↩

-

American Indian Airwaves podcast, 2022. Protecting Chi’chil Bildagoteel: The Apache Stronghold Spiritual Convoy. https://soundcloud.com/burntswamp/protecting-chichil-bildagoteel-oak-flat-the-apache-stronghold-spiritual-convoy ↩

-

Indigenous Goddess Gang, 2018. Land, Water, Dignity: Protecting Chich’il Bildagoteel (Oak Flat). https://www.indigenousgoddessgang.com/land-water-dignity-1/2018/5/14/protecting-chichil-bildagoteel-oak-flat ↩

-

San Carlos Apache Tribe Joint Press Release, 2012. ↩

-

Talbot, Steve. “Spiritual Genocide: The Denial of American Indian Religious Freedom, from Conquest to 1934.” Wicazo Sa Review, vol. 21, no. 2, 2006, pp. 7–39. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4140266. Accessed 22 Feb. 2023. ↩

-

Becket Law, 2021. Apache Stronghold v. United States case detail. https://www.becketlaw.org/case/apache-stronghold-v-united-states/ ↩

-

Constitution of the United States. Library of Congress. https://constitution.congress.gov/constitution/amendment-1/ ↩

-

Talbot, 2006, as quoted in the 1928 Meriam Report ↩

-

Margaret Conell Szasz, 1981. “Federal Boarding Schools and the Indian Child: 1920-1960,” in The American Indian, Past and Present. New York: John Wiley and Sons. p 215-217. ↩

-

Luis Rivera, 1992. A Violent Evangelism. Louisville: Westminster Press. ↩ ↩2

-

Eyewitness History, 1999. Battle with the Apache, 1872. http://www.eyewitnesstohistory.com/apache.htm ↩

-

D’Errico, Peter, 2016. Oak Flat Violates Apache Rights and Mining Best Practices. Indian Country Today Media Network https://www.academia.edu/23834985/Oak_Flat_Deal_Violates_Apache_Rights_and_Mining_Best_Practices ↩

-

Morman, Todd Allin, 2016. Thesis Dissertation. Indian sovereignty and religious freedom: United States public land management and Indian sacred sites, 1978-2014; University of Missouri-Columbia; p 286. ↩

-

Millet, “Selling Off Apache Holy Land,” as quoted in Joseph Huff-Hannon, 2015, Rolling Stone News. “Meet the Apache Activists Opening for Niel Young,” Rolling Stone, July 21, 2015. http://www.rollingstone.com/politics/news/meet-the-apacheactivists-opening-for-neil-young-20150721 ↩

-

Treaty with the Apache, 1 July 1852. Yale Law School Avalon Project. https://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/apa1852.asp ↩

-

Apache Stronghol v. United States of America, 2022. https://cdn.ca9.uscourts.gov/datastore/opinions/2022/06/24/21-15295.pdf ↩

-

Becket Law, 2021. Oak Flat: A holy land worth fighting for. YouTube video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2aJK0Tko28M ↩

SUGGESTED CITATION

Luke Henkel, "Oak Flats and the Doctrine of Discovery unprecedented challenge and opportunity," Doctrine of Discovery Project (23 March 2023), https://doctrineofdiscovery.org/blog/oak-flats/.

Donate today!

Open Access educational resources cost money to produce. Please join the growing number of people supporting The Doctrine of Discovery so we can sustain this work. Please give today.