Part 1: The Origins of the Combahee River Collective Statement

Introduction

“Asia, Africa, and Europe all meet in the Americas to labor over the dialectics of free and unfree, but what of the Americas themselves and the prior peoples upon whom that labor took place?” ~Jodi Byrd, Transit of Empire: Indigenous Critiques of Colonialism

[A prayer] that “ we might come to know, love, and care for one another with deeper and more rigorous intimacy.” ~brontë velez

In the 1600s when enslaved Africans disembarked en masse and travel weary to this land mass, they arrived in a place where hundreds of Indigenous groups lived since time immemorial.1 Since that moment The majority of the interactions between Black people and Indigenous Peoples living in the so-called United States occur(red) in the bloody context of settler colonial imperialism. Black people were kidnapped, trafficked, enslaved, segregated, imprisoned, and assassinated by individuals and a system that did not value our personhood, but sought to exploit our bodies and souls.2 Indigenous peoples were (and continue to be) exploited, infected, schooled, silenced, relegated, and murdered by individuals and a system that did not (and does not) value their personhood, but sought (and seeks) to erase their bodies and souls.3 In the 21st century, both remain tolerated but targeted, appropriated, and tokenized.4

In response to lived conditions, feminisms developed in various Black and Indigenous communities as part of resisting settler-colonialism, racism, sexism, capitalism and classism, and other forms of oppression. Feminist movements in Black and Indigenous communities have been proximate, overlapping, and mutually reinforcing, but also at times in tension with one another. Though both expansive areas of collective work, Black feminisms and Indigenous feminisms tend to center different aspects of the struggle for liberation. Some strain between movements comes from the inadvertent solidification of the settler state that can happen as some Black feminists struggle for their freedom and self-determination within the settler state without explicitly articulating an analysis of settler colonialism. Other tensions come from some Indigenous feminists’ refusal of participation in solidarity politics in a way that weakens ‘BIPOC’ coalitions facing repression, and various expressions of uninterrogated antiblackness. This paper posits that the Doctrine of Discovery (DoD), a 15th century set of religious and state decrees that facilitated Christian European global exploration and expropriation, is a ripe site to analyze together for both Indigenous and Black feminist organizers because it allows for the incorporation of an analysis of settler colonialism without de-centering issues that are essential to Black feminist theory and practice. As a Black feminist organizer with some experience organizing alongside Indigenous feminists, this set of four blogs will:

- Examine the absence of a settler colonial analysis in two moments in the theoretical lineage of US Black feminism–the Combahee River Collective statement of 1977 and the Allied Media Conference AfroFeministFutures panel in 2022.

- Explore opportunities presented for the inclusion of a settler colonial analysis

- Analyze how engaging the Doctrine of Discovery can be a way Black feminists incorporate an analysis of settler colonialism without de-centering the issues that are essential to Black feminist theory and practice.

- Imagine a future in which Black and Indigenous Feminisms make common cause, for the purpose of healing our lineages, and practicing the liberatory politics we aspire.

The Origins of the Combahee River Collective Statement

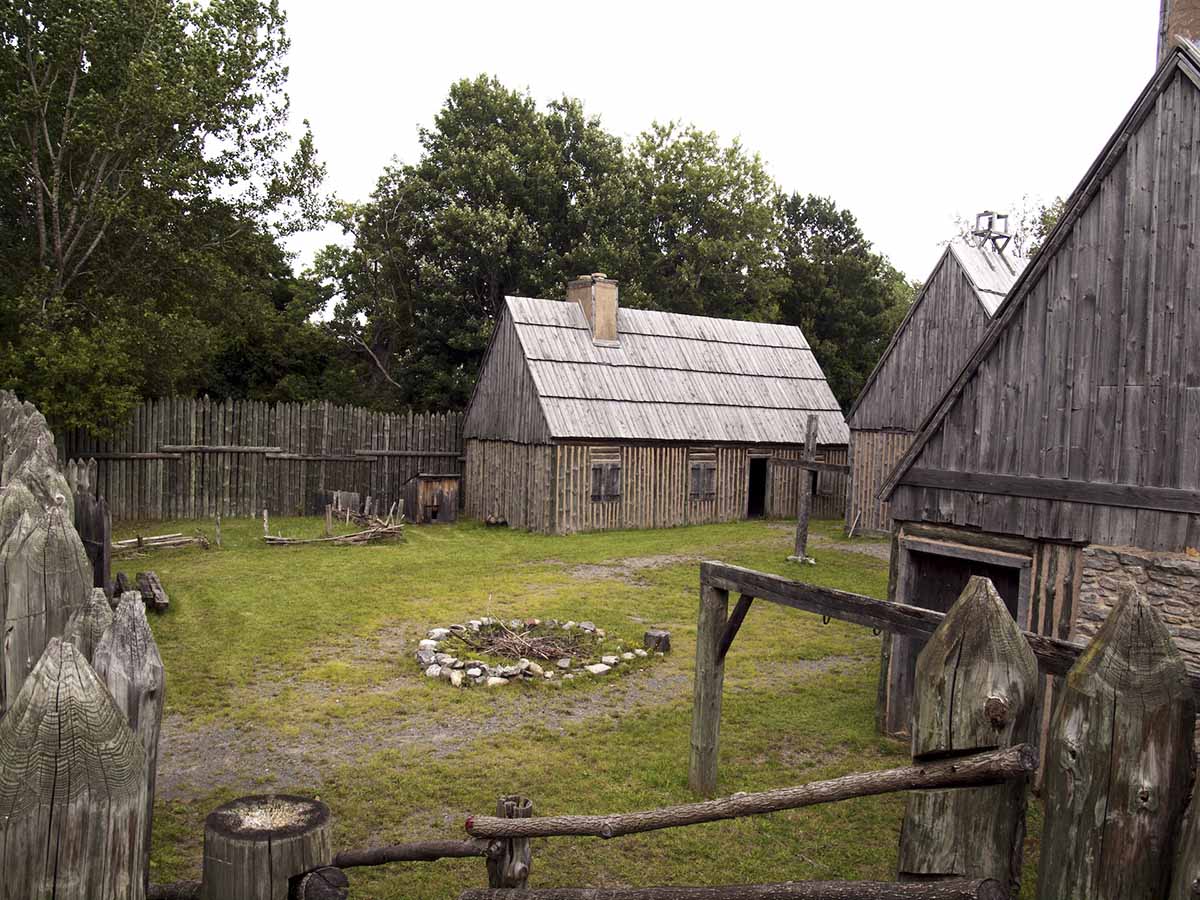

50 miles from Charleston, South Carolina, is the mouth of the Combahee River, named for the Indigenous people of the place. It was home to numerous plantations where Black people were forced into the institution of slavery. Just after the Revolutionary war battles fought in the area, this fecund place supplied vast amounts of water for some of the new country’s largest rice plantations, producing immense wealth for European-Americans (who now understood themselves to be white); returning none to the Indigenous Peoples, lands, and trafficked African laborers (now categorized as Black people) there. Indigenous and Black people repeatedly rebelled against the coercion, despite the punishing violence white people perpetuated upon them in order to maintain possession and build the US nation-state. Some of the early interactions between Black and Indigenous people happened in captivity in military forts–shared cells of incarceration for resistance to white possession of land, labor, and life.5 It was at the Combahee River that Harriet Tubman led a Union Army regiment in a raid that destroyed millions of dollars of supplies going to the Confederate Army and freed over 750 enslaved Africans. This rebellion would be an inspiration to a quintessential Black feminist group over a century later.

Black feminism is an ideology of Black women’s (and those read as Black women) inherent worth and a practice of liberation of Black women and their communities from all oppression. It is a response to an anti-black, anti-female status quo. Through organizations, statements, political coalitions, and other forms of solidarity building and change-making, Black feminism confronts the interlocking systems of oppression of Black people (and others multiply oppressed and marked by the structures of white supremacist cisgendered heteropatriarchy) worldwide and offers an alternative vision for society. The common articulation of the movement traces its origin to resistance to enslavement and the particular ways that the institution impacted Black females. Regardless of their personal gender expression, they were gendered as women and experienced sexism. The sexual violence perpetrated against Black women in the context of the plantation and the impunity for white men, white women, and Black men who committed it created a devastating type of isolation. This dehumanization resulted in the articulation of a political framework that challenged the white feminist movement (in which racism existed), and the Black civil rights community (in which patriarchy existed), as well as broader society.6

The Combahee River Collective, as a specific Black feminist formation, lasted six years and was active in the Boston area from 1974-1980. In 1977, members Demita Frazier, Barbara and Beverly Smith, penned a statement that has become a central touchstone of the Black Feminist movement. Their self-description and reason for writing states:

We are a collective of Black feminists who have been…involved in the process of defining and clarifying our politics, while at the same time doing political work within our own group and in coalition with other progressive organizations and movements. The most general statement of our politics at the present time would be that we are actively committed to struggling against racial, sexual, heterosexual, and class oppression, and see as our particular task the development of integrated analysis and practice based upon the fact that the major systems of oppression are interlocking. The synthesis of these oppressions creates the conditions of our lives. As Black women we see Black feminism as the logical political movement to combat the manifold and simultaneous oppressions that all women of color face.7

The powerful statement of liberation was a strategic move named in honor of Harriet Tubman, a Black woman whose powerful strategy generated liberation. Taking action to rupture society’s operations in order to create space and safety for oneself and all oppressed others in order to generate change is Combahee’s legacy.

Within the 4,000+ word statement, the writers focus on the genesis of contemporary Black feminism, their Collective’s politics, beliefs, practices, issues, and the difficulties for Black feminists as they organize. The end of the introduction features the following paragraph:

We might use our position at the bottom, however, to make a clear leap into revolutionary action. If Black women were free, it would mean that everyone else would have to be free since our freedom would necessitate the destruction of all the systems of oppression.8

Throughout the next four decades Black feminist organizing has taken many forms as it combats “the manifold and simultaneous oppressions that women of color face.”9 It’s intellectual contributions include Kimberlé Crenshaw’s Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex law review article which coined the term intersectionality, Pauli Murray’s genius contributions to the world, Toni Cade Bambara and followers in the arts, Audre Lorde, bell hooks, Assata Shakur, the Spelman College Comparative Women’s Studies program, and many more today.10 The Black Lives Matter, and #MeToo movements are also powerful grassroots expressions of the leap into revolutionary action invited by Black feminism and the Combahee River Collective and their antecedents.

The writers did not explicitly address the settler colonial context in which they were writing, or in which Harriet was fighting. They wrote that they saw themselves at the bottom of society, as exploited Black female queer laborers. Critical Indigenous Studies scholar Jodi Byrd invites going a layer under the bottom. “But what of the Americas themselves and the prior peoples upon whom that labor took place? Byrd asks.”11 This question is poignant because the liberal settler colonial nation-state is interested in shoring up its existence by finding ways to incorporate racialized populations to see their future within it. Many “diversity, equity, inclusion, and justice” efforts function to reify the state even while supposedly challenging it. Though for Black feminists the politics of representation has never been the main focus–rather the self-determination and wellbeing of our communities–the presence of the state and its functionaries was taken as a given. For Indigenous feminists, the theorizing against and beyond the settler colonial state itself, toward sovereignty and nationhood is key.12 Using the imagery of perpetual cacophony that makes it difficult to orient oneself amidst noise, Byrd articulates the nation-states deflection and attention clouding:

As liberal multicultural settler colonialism attempts to flex the exceptions and exclusions that first constituted the United States to now provisionally include those people othered and abjected from the nation-state’s origins, it instead creates a cacophony of moral claims that help to deflect progressive and transformative activism from dismantling the ongoing conditions of colonialism that continue to make the United States a desired state formation within which to be included.

That cacophony of competing struggles for hegemony within and outside institutions of power, no matter how those struggles might challenge the state through loci of race, class, gender, and sexuality, serves to misdirect and cloud attention from the underlying structures of settler colonialism that made the United States possible as oppressor in the first place. As a result, the cacophony produced through U.S. colonialism and imperialism domestically and abroad often coerces struggles for social justice for queers, racial minorities, and immigrants into complicity with settler colonialism.13

This treacherous reality is why it is important that even Black feminists explicitly articulate that settler colonialism is one of the interlocking systems of oppression. This elision in the Combahee River Collective statement leaves open the door for the US nation-state to co-opt Black feminism.

Allied Media Conference Panel: AfroFeministFutures

A generation later, in 2022, the AfroFeministFutures panel at the Allied Media Conference (AMC) drew on the Combahee River Collective’s statement in order to theorize for the future.14 As the opening panel to the most highly respected conference in young leftist activist circles, the selection of this topic reaffirmed how Black feminist principles and organizing are seen as the foundation for transformative possibilities and sharp analysis. All three of the Combahee River Collective statement writers are still alive. One, Demita Frazier, JD was on the panel and created an energizing linkage between eras. She was joined by Paris Hatcher of Black Feminist Futures, Emmanuelle ‘Emani’ Love of Wage Love Apothecary, Asha Ransby-Sporn of Chicago’s Black Youth Project (BYP100) fame and Dissenters antimilitarism effort. The panel was moderated by Dr. Moya Bailey, author of Misogynoir Transformed: Black Women’s Digital Resistance.15

The panel began with a robust acknowledgement of the place of Detroit–the land (how it was stolen and the Indigenous people who call it home) and the waves of settlement by arrivants, immigrants, settlers, refugees, and their combinations. The acknowledgement also spoke of liberation practices that took place in Detroit, ostensibly to locate the AMC in this tradition. The first question asked the panelists which systems of oppression does the Black feminist work they do actively seek to destroy? The answers included combating:

- Policing, incarceration, and militarism (as the violent and armed part of the state that actively works to keep white supremacy, patriarchy, and capitalism/neoliberalism in place through violence or threats of violence)

- Individualism and perfectionism (cultural manifestations of heteropatriarchal white supremacy)

- Misogynoir and transmisogynoir (the particular type of intersectional hatred that Black women and Black trans folks face)

- Structural racism

- Homelessness

- Spiritual injustice (trauma inflicted by dominant Christian thinking)

Their answers reflected issues on which they specialize, even as they make common cause with broader movements. Other key points from the panel included:

- Recognizing that the Black community is actually multiple communities, not a monolith.

- Inviting non-Black allies to de-center themselves as they seek to be in solidarity

- Examining the risks involved in dismantling white supremacy

- Doing the very difficult healing of internalized inferiority within oneself

- Highlighting stories as the foundation for building political campaigns and understanding issues

- Resisting tokenism and learning from the most marginalized

- Encouraging a shift away from state-centered solutions and activism, and shifting our relationships to one another in the process

Destroying settler colonialism, or noting it as one of the interlocking systems of oppression did not happen in direct response to any question. The word decolonization was used only twice during the panel: once emphasizing the need to decolonize the spirit, and another time in reference to the mind. While critical thinking and spiritual agency are important, these uses do not refer to the return of land to indigenous people. Tuck and Wang, authors of Decolonization is Not a Metaphor have cautioned against using the word decolonization in North America when speaking about anything other than the distinct project of disordering the colonial world.16 When used as metaphor, it often functions as signaling “both an awareness of the significance of Indigenous and decolonizing theorizations” but to include them in another struggle. This can downplay the incommensurability of efforts for recognition and/or sovereignty with those of civil and/or human rights struggles. Following Arvin, Tuck, and Morrill, it is important to craft alliances that directly address differences.”17

Resources

References ———-

-

AfroFeministFutures For the World We Want. Allied Media Conference, Allied Media Project, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iYM0Jf4mWjE

-

Arvin, Maile, Eve Tuck, and Angie Morrill. “Decolonizing feminism: Challenging connections between settler colonialism and heteropatriarchy.” Feminist formations(2013): 8-34.

-

Beloved Community, Asheville, North Carolina. https://becomingbelovedcommunity.org/doctrine-of-discovery.

-

Black Women Radicals www.blackwomenradicals.com

-

Byrd, Jodi A. The transit of empire: Indigenous critiques of colonialism. U of Minnesota Press, 2011.

-

Collective, Combahee River. “The Combahee river collective statement.” (self-published in 1977), cited in Words of Fire: An Anthology of African American Feminist Thought, ed. Beverly Guy-Sheftall (New York: New Press, 1995), 233.

-

Gilmore, Ruth Wilson. Golden gulag: Prisons, surplus, crisis, and opposition in globalizing California. Vol. 21. Univ of California Press, 2007.

-

Hayes, Kelly. “How to Talk about #NoDAPL: A Native Perspective.” Truthout, October 28, 2016. Retrieved from: https://truthout.org/articles/how-to-talk-about-nodapl-a-native-perspective/.

-

hooks, bell. All about love: New visions. Harper Perennial, 2001.

-

Indigenous Feminist Power Panel, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-HnEvaVXoto.

-

King, Tiffany Lethabo with brontë velez, “On the Black Shoals: Part 2” For the Wild. December 14, 2022, https://forthewild.world/listen/tiffany-lethabo-king-on-the-black-shoals-316.

-

Kivel, Paul. Living in the shadow of the cross: Understanding and resisting the power and privilege of Christian hegemony. New Society Publishers, 2013.

-

LANDBACK Manifesto. https://landback.org/manifesto/.

-

Lawrence, Bonita, and Enakshi Dua. “Decolonizing antiracism.” Social justice4 (102 (2005): 120-143.

-

Miller, Robert J., et al. Discovering indigenous lands: The doctrine of discovery in the English colonies. Oxford University Press, 2010.

-

Moreton-Robinson, Aileen. “Writing Off Treaties” Chapter 4 in The white possessive: Property, power, and indigenous sovereignty. U of Minnesota Press, 2015.

-

Tuck, Eve, and K. Wayne Yang. 2012. “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society1: 1-40.

-

Wolfe, Patrick. “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native.” Journal of genocide research4 (2006): 387-409.

-

Doctrine of Disovery Papal Bulls: Dum Diversas 18 June, 1452, The Bull Romanus Pontifex (Nicholas V), January 8, 1455 and The Bull Inter Caetera (Alexander VI), May 4, 1493. Later expansions of these bulls include the Treaty of Tordesillas, June 7, 1494, the Patent Granted by King Henry VII to John Cabot and his Sons, March 5, 1496, The Requerimiento, 1514. https://doctrineofdiscovery.org/.

Footnotes

-

There are numerous timeframes in which to locate the beginning of settler-colonialism. Tarren Andrews, for example, dates it to the Medieval era. 1492 represents a particular type of rupture as well. I choose 1600 because of the sheer volume of “commerce” moving across the Atlantic in toxic triangles and quadrilaterals by this point in time. Furthermore, there are numerous ways to name both Indigenous connections to place while recognizing shared evolutionary history, without destabilizing Indigenous connections. Indigenous Peoples are connected to their homelands in an indissoluble, irreducible way, and in ways very different than European settler-colonists. I do not see this as a contradiction to the shared human evolutionary history of ancient migration of everyone from the Great Rift Valley in what is now called eastern Africa. People walked from there all over the world, and became some of the first humans to relate to all sorts of different lands and waters, to become indigenous to those places. As the timescales are vastly different (10,000 years ago vs. 1000 years ago), and “time immemorial” refers to “the time we collectively remember”. Numerous indigenous groups on Turtle Island, for example, do not have a collective memory of the trek from Africa and their stories begin with them located en situ. Though the collective trek happened, sharing that information with Indigenous Peoples whose origin stories state otherwise should not be used to displace their claim of being aboriginal to their homelands, instead, only used to recognize the ultimate kinship among humans (homo sapiens) making all people deserving of mutual recognition as persons. Personhood, and relatedly, belonging through kinship or social circumstances, has not always been afforded to people of African descent, both within and outside of some Indigenous communities. ↩

-

Hayes, Kelly. “How to Talk about #NoDAPL: A Native Perspective.” Truthout, October 28, 2016. Retrieved from: https://truthout.org/articles/how-to-talk-about-nodapl-a-native-perspective/. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

As an author who primarily identifies ethnically as a person of African descent, I will use personal or collective pronouns when speaking about Black people and our experience. Like many “African-Americans”, I have ancestors who are “Native-Americans.” That history and those connections were not kept alive in my immediate or extended families. Therefore, I employ the third person singular and plurals when referring to indigenous people and their experiences. ↩

-

King, Tiffany Lethabo with brontë velez, “On the Black Shoals: Part 2” For the Wild. December 14, 2022, https://forthewild.world/listen/tiffany-lethabo-king-on-the-black-shoals-316. ↩

-

In regards to the white feminist movement: while originally inspired by native women’s powerful positions in their own communities and supported by coalition of abolitionists, ultimately the mainstream feminist movement chose to privilege its proximity to white supremacist patriarchy and disavowed and participated in the oppression of Indigenous, Black, and other people of color. ↩

-

Collective, Combahee River. “The Combahee river collective statement.” (self-published in 1977), cited in Words of Fire: An Anthology of African American Feminist Thought, ed. Beverly Guy-Sheftall (New York: New Press, 1995), 233. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Combahee River Collective statement. ↩

-

See www.blackwomenradicals.com for an ongoing web archive. ↩

-

Byrd, Jodi A. The transit of empire: Indigenous critiques of colonialism. U of Minnesota Press, 2011, xxv. ↩

-

Lawrence, Bonita, and Enakshi Dua. “Decolonizing antiracism.” Social justice 32.4 (102 (2005): 120-143. ↩

-

Byrd, Transit of Empire, xvii. ↩

-

AfroFeministFutures For the World We Want. Allied Media Conference, Allied Media Project, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iYM0Jf4mWjE ↩

-

The AfroFeministFutures panel at AMC focused on what these Black feminists are working on, and their thoughts about the future. There were parallels between it and the Indigenous Feminist Power Panel that occurred at the University of Saskatchewan in 2016. Both featured individuals who bring a feminist analysis to their work in whatever sector they are in. Both Black and Indigenous feminisms have become an area of academic and popular study, and the panels focused on the political organizing and direct action efforts that generated material for the emerging field to study. In both cases, scholarship in Indigenous and Black feminists reciprocally informs ongoing feminist political organizing. Indigenous Feminist Power Panel: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-HnEvaVXoto. ↩

-

Tuck, Eve, and K. Wayne Yang. 2012. “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1.1: 1-40. ↩

-

Arvin, Maile, Eve Tuck, and Angie Morrill. “Decolonizing feminism: Challenging connections between settler colonialism and heteropatriarchy.” Feminist formations (2013): 8-34. ↩

SUGGESTED CITATION

Sarah Nahar, "Part 1: The Origins of the Combahee River Collective Statement," Doctrine of Discovery Project (8 May 2023), https://doctrineofdiscovery.org/blog/river/combahee-river/.

Share on

Twitter Facebook LinkedInDonate today!

Open Access educational resources cost money to produce. Please join the growing number of people supporting The Doctrine of Discovery so we can sustain this work. Please give today.