Part 3: Using the Doctrine of Discovery to Foreground an Analysis of Settler Colonialism

Introduction

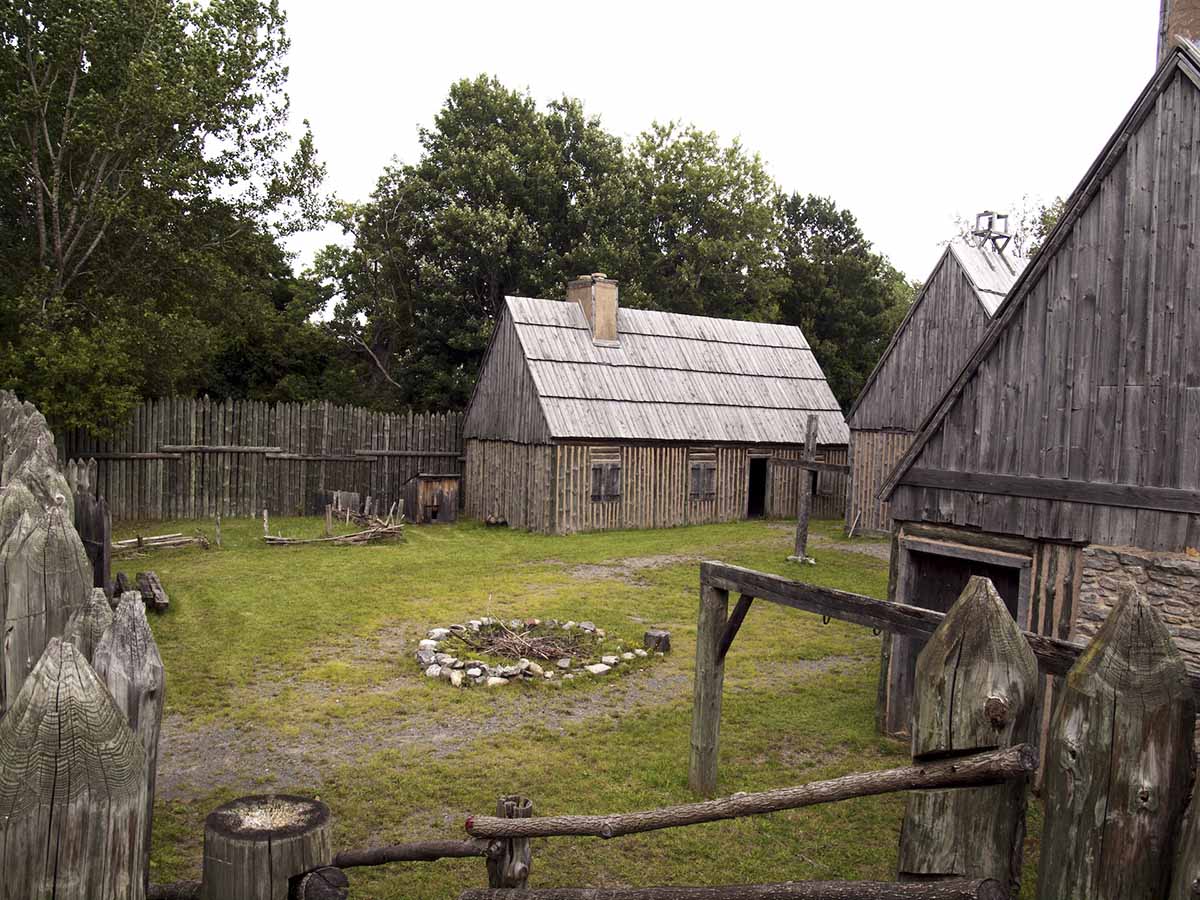

In the 1600s when enslaved Africans disembarked en masse and travel weary to this land mass, they arrived in a place where hundreds of Indigenous groups lived since time immemorial.1 Since that moment The majority of the interactions between Black people and Indigenous Peoples living in the so-called United States occur(red) in the bloody context of settler colonial imperialism. Black people were kidnapped, trafficked, enslaved, segregated, imprisoned, and assassinated by individuals and a system that did not value our personhood, but sought to exploit our bodies and souls.2 Indigenous peoples were (and continue to be) exploited, infected, schooled, silenced, relegated, and murdered by individuals and a system that did not (and does not) value their personhood, but sought (and seeks) to erase their bodies and souls.3 In the 21st century, both remain tolerated but targeted, appropriated, and tokenized.4

In response to lived conditions, feminisms developed in various Black and Indigenous communities as part of resisting settler-colonialism, racism, sexism, capitalism and classism, and other forms of oppression. Feminist movements in Black and Indigenous communities have been proximate, overlapping, and mutually reinforcing, but also at times in tension with one another. Though both expansive areas of collective work, Black feminisms and Indigenous feminisms tend to center different aspects of the struggle for liberation. Some strain between movements comes from the inadvertent solidification of the settler state that can happen as some Black feminists struggle for their freedom and self-determination within the settler state without explicitly articulating an analysis of settler colonialism. Other tensions come from some Indigenous feminists’ refusal of participation in solidarity politics in a way that weakens ‘BIPOC’ coalitions facing repression, and various expressions of uninterrogated antiblackness. This paper posits that the Doctrine of Discovery (DoD), a 15th century set of religious and state decrees that facilitated Christian European global exploration and expropriation, is a ripe site to analyze together for both Indigenous and Black feminist organizers because it allows for the incorporation of an analysis of settler colonialism without de-centering issues that are essential to Black feminist theory and practice. As a Black feminist organizer with some experience organizing alongside Indigenous feminists, this set of four blogs will:

- Examine the absence of a settler colonial analysis in two moments in the theoretical lineage of US Black feminism–the Combahee River Collective statement of 1977 and the Allied Media Conference AfroFeministFutures panel in 2022.

- Explore opportunities presented for the inclusion of a settler colonial analysis

- Analyze how engaging the Doctrine of Discovery can be a way Black feminists incorporate an analysis of settler colonialism without de-centering the issues that are essential to Black feminist theory and practice.

- Imagine a future in which Black and Indigenous Feminisms make common cause, for the purpose of healing our lineages, and practicing the liberatory politics we aspire.

Using the Doctrine of Discovery to Foreground an Analysis of Settler Colonialism

The Doctrine of Discovery (DoD, sometimes called the Doctrine of Christian Domination) is considered a major root of settler colonialism globally. The DoD is a set of 15th-century Catholic Papal Bulls that condoned the invasion, capture, murder, kidnapping and enslavement of anyone non-Christian.5 Even before wreaking massive havoc on the peoples and ecosystems of the so-called Americas, the Doctrine of Discovery justified the Christian conquest over and mistreatment of Muslims (Saracens) and invasion of the lands of African peoples (pagans) and all of their lands. African countries and communities continue to suffer due to colonization and imperialism. And this set of religious documents that made their way into so-called secular legal frameworks in the US and elsewhere govern the lives of millions of Black people. There isn’t an area of life untouched by the DoD. It influences the legal, carceral, educational, health care, and economic system, to name a few of the interlocking systems of oppressions it legitimizes.

The oft cited paragraph from 1452 Dum Diversas instructs Christian explorers on what to do if they found land where no European Christians were living. They were to

…invade, search out, capture, vanquish, and subdue all Saracens and pagans whatsoever, and other enemies of Christ wheresoever placed, and the kingdoms, dukedoms, principalities, dominions, possessions, and all movable and immovable goods whatsoever held and possessed by them and to reduce their persons to perpetual slavery.6

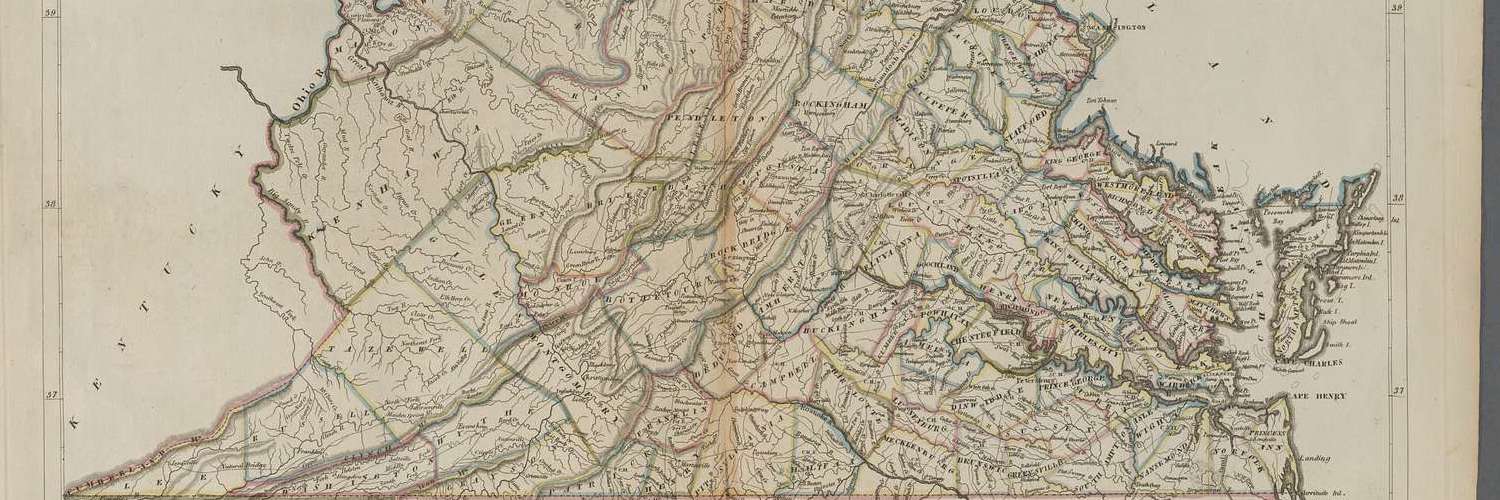

In the US the DoD’s codification into law occurred in 1823 when the Supreme Courts enshrined it through its decision of Johnson v M’Intosh making the government the only eligible sellers of Native land title. Even earlier, in the 1790-1793 writings of Thomas Jefferson, the DoD was used as justification for claiming the Pacific Northwest, as well as negotiating with France and Spain around the massive purchase of land from them (without regard for Native sovereignty and life in those areas).7 As recently as 2005 the DoD was cited by the Supreme Court, and the DoD itself has not been repudiated by the Catholic Church. Numerous Indigenous activists and their allies have been working in disparate locations and institutions (ecclesial and otherwise) to try to build a movement to dismantle the DoD. The budding movement holds conferences and does base-building activities. It is gaining momentum and envisages itself mobilizing a broad base. It is a space for Black feminists to learn and contribute as the discourse will be greatly enhanced by the participation of a critical number of Black feminists.

The first DoD decree issued in 1452 enabled Portuguese sailors to invade the homes and lands of Indigenous Peoples in west Africa: to plunder their relations, to kidnap and enslave them. Until forcibly baptized, Africans were not seen as human, and therefore the land was considered empty of humans (terra nullius), and available for “resource extraction” by the Portuguese crown. As Portugal lost power, other European nations justified by the power of the DoD laid claim to the same lands (and more!) of Indigenous Africans, possessing it and all “moveable and immovable goods.” Indigenous Africans, like Indigenous Peoples in the so-called Americas, were considered moveable goods and real estate. Slavery became an economic engine, moving these “goods and real estate” across the Atlantic.

While slavery takes up significant space in our imaginary as African diasporic peoples living in the US, recognizing the harm settler colonialism, via the DoD, caused to us as indigenous peoples can help us get back in touch with our own indigeneity and sense of land connection. However distant in the past, it did exist. Whether or not we remember the land skills of our ancestors, King maintains that wherever we are, “the land is making space for you. It remembers you. It is calling you and pulling you towards it.”8 Our communities lived in ways that were reciprocal, regenerative, and relational with the environments they had known for thousands of years. The wound of being torn from those is incalculable. Whether or not our indigeneity was fully eliminated in this process remains an open and heartbreaking question. In addition to the violence of separation from one’s sovereign home, plantation slavery in Brazil, the Caribbean, and the US extracted labor from Black bodies as part of projects of extraction from the Earth. This caused trauma to both entities and forged a traumatic relationship between them. Gesturing back to and extending Emani Love’s comment on the panel, healing Black relationship to land is rebellion against settler colonial racial capitalism which sought to break it.

The ability of police to kill with near total impunity both Black and Indigenous people today is evidence of the DoD, as is the violent state repression when either community mobilizes for self-determination. The DoD document Requerimiento reveals the blueprint. It was read to peoples whose lands were being encountered by the Spanish for the first time. If an Indigenous community did not willingly surrender their land, liberty, and lifeways, and convert to European Christianity, the following would happen:

We will take you and your wives and children and make them slaves, and as such we will sell them, and will dispose of you and them as Their Highnesses order. And we will take your property and will do to you all the harm and evil we can, as is done to vassals who will not obey their lord or who do not wish to accept him, or who resist and defy him. We avow that the deaths and harm which you will receive thereby will be your own blame, and not that of Their Highnesses, nor ours, nor of the gentlemen who come with us.”9

This sentiment is echoed in ‘Virginia Slave Codes’ two centuries later, which both racially codified slavery and permitted violence against racialized people:

All servants imported and brought into the Country…who were not Christians in their native Country…shall be accounted and be slaves. All Negro, mulatto and Indian slaves within this dominion… shall be held to be real estate. If any slave resist his master… correcting such slave, and shall happen to be killed in such correction…the master shall be free of all punishment…as if such accident never happened.10

These documents form the basis of the US legal system, law enforcement, segregation, and gentrification–they are rooted in the past and ongoing systems of oppression. The frameworks for punishment for resistance, baked-in impunity for law enforcement, and the entire prison system is built on the supremacies generated by the DoD. Note the italics above as to lack of culpability for the Europeans. Locating the fight to defund the police in a settler colonial, as well as race-based, framework allows for a deeper analysis than racial hatred to understand why the system is so entrenched, and what strategies will be required to abolish it. There is a growing body of literature on police and prison abolition. Lots of exciting opportunities—due to terrifying conditions—for Black and Indigenous feminists and carceral abolitionists to connect to produce knowledge together. One such example of this is the new book (May 2023 release date) by Kelly Hayes and Miriam Kaba, called Let This Radicalize You: Organizing and the Revolution of Reciprocal Care. I am looking forward to see how the DoD is addressed, if at all.

The Slave Codes later morph into Black Codes that go in effect after emancipation. These Codes control the movement of Black people and create a police state to monitor Black conduct and punish any form of “deviance.” This leads to segregation, which further solidifies white society’s self-referentiality and supremacy thinking due to separation and spatial power (in rural and urban spaces). In the last century this meant redlining, divestment, and programs such as urban renewal. In the contemporary era this means gentrification. The connection back from gentrification to the DoD is that the DoD is a document of entitlement to claim any place they want to live, and go live there. Still today many white people feel they are entitled to live anywhere they want, claiming it for themselves and, often, changing the historic character of the space (be it a continent, country, or neighborhood). Like the European Christian explorers before them they see themselves as “improving and investing” while ignoring or repressing the resistance from residents along the way.

The DoD is a legal, cultural, and economic framework that came from a particular religious tradition. Religion (defined as a set of stories, orientations, rituals, and meaning making activities) is visible in the DoD. Therefore, it’s a vital and often overlooked site of analysis that is necessary to include in and analyze as any part of a genealogy of white supremacy. Furthermore, race, as a social construction co-developed with modern Christian religious thinking, which also co-developed with colonialism. Paul Kivel, Jewish anti-violence educator, author, and activist writes:

Researching the history of racism led me to understand that before Europeans understood themselves to be white they thought of themselves as Christian. Jews, Pagans and Muslims were the long-standing Others. When encountered, [Indigenous Peoples] and Africans became new heathens in the same good/evil equation. It was only when some Jews and Muslims, and subsequently [Indigenous Peoples] and enslaved Africans, began to convert to Christianity that white Christians felt the need to draw an uncrossable line. Even if members of these groups became Christian, they would still be ineligible for participation in society because they were not white. Being a white Christian (and a cishet man) became the criterion for being fully human.11

Since many Black folks have experience with the Christian church, understanding this historical background offers an opportunity to interrogate various religious inheritances. It is important to interrogate what aspects of Christianity, mediated through white supremacy, have influenced the ways Black Christians understand themselves, their theology and ethics. Some of the things considered essential to the faith have little to do with its indigenous wisdom tradition orientations in the ancient near east, and more to do with European interpretations of the previously pacifist and communal faith practices. A few examples include negative views of the naked body, constructions of masculinity and femininity, dance, and the nuclear family structure.

Though there were continental Africans who were Christian before being trafficked and enslaved, most Black folks encountered the Christian church in the context of enslavement. It was generally used by white Christians in an attempt to pacify enslaved peoples. Upon reading the Biblical text, however, many connected to the stories of liberation therein. Most of the biblical stories are codified oral tradition from other indigenous groups. Issues of slavery, proto-settler colonialism, conquest, and other themes appear in the complication of texts considered “Holy Scriptures” by many. For Black feminists involved in organizing communities of faith, there is an opening here to de-westernize Christianity and re-situate the Bible as a product of the northern African and eastern Mediterranean geopolitical and cultural contexts.

There are more reasons to use the DoD as a way to integrate an analysis of settler colonialism into Black feminism. They will emerge once Black feminists begin to wrestle with the DoD and its implications. Since Black feminism is grounded in practical action, integrating the analysis of settler colonialism will lead to actions informed by it.

References

-

AfroFeministFutures For the World We Want. Allied Media Conference, Allied Media Project, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iYM0Jf4mWjE

-

Arvin, Maile, Eve Tuck, and Angie Morrill. “Decolonizing feminism: Challenging connections between settler colonialism and heteropatriarchy.” Feminist formations(2013): 8-34.

-

Beloved Community, Asheville, North Carolina. https://becomingbelovedcommunity.org/doctrine-of-discovery.

-

Black Women Radicals www.blackwomenradicals.com

-

Byrd, Jodi A. The transit of empire: Indigenous critiques of colonialism. U of Minnesota Press, 2011.

-

Collective, Combahee River. “The Combahee river collective statement.” (self-published in 1977), cited in Words of Fire: An Anthology of African American Feminist Thought, ed. Beverly Guy-Sheftall (New York: New Press, 1995), 233.

-

Gilmore, Ruth Wilson. Golden gulag: Prisons, surplus, crisis, and opposition in globalizing California. Vol. 21. Univ of California Press, 2007.

-

Hayes, Kelly. “How to Talk about #NoDAPL: A Native Perspective.” Truthout, October 28, 2016. Retrieved from: https://truthout.org/articles/how-to-talk-about-nodapl-a-native-perspective/.

-

hooks, bell. All about love: New visions. Harper Perennial, 2001.

-

Indigenous Feminist Power Panel, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-HnEvaVXoto.

-

King, Tiffany Lethabo with brontë velez, “On the Black Shoals: Part 2” For the Wild. December 14, 2022, https://forthewild.world/listen/tiffany-lethabo-king-on-the-black-shoals-316.

-

Kivel, Paul. Living in the shadow of the cross: Understanding and resisting the power and privilege of Christian hegemony. New Society Publishers, 2013.

-

LANDBACK Manifesto. https://landback.org/manifesto/.

-

Lawrence, Bonita, and Enakshi Dua. “Decolonizing antiracism.” Social justice4 (102 (2005): 120-143.

-

Miller, Robert J., et al. Discovering indigenous lands: The doctrine of discovery in the English colonies. Oxford University Press, 2010.

-

Moreton-Robinson, Aileen. “Writing Off Treaties” Chapter 4 in The white possessive: Property, power, and indigenous sovereignty. U of Minnesota Press, 2015.

-

Tuck, Eve, and K. Wayne Yang. 2012. “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society1: 1-40.

-

Wolfe, Patrick. “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native.” Journal of genocide research4 (2006): 387-409.

-

Doctrine of Disovery Papal Bulls: Dum Diversas 18 June, 1452, The Bull Romanus Pontifex (Nicholas V), January 8, 1454 and The Bull Inter Caetera (Alexander VI), May 4, 1493. Later expansions of these bulls include the Treaty of Tordesillas, June 7, 1494, the Patent Granted by King Henry VII to John Cabot and his Sons, March 5, 1496, The Requerimiento, 1514. https://doctrineofdiscovery.org/.

Footnotes

-

There are numerous timeframes in which to locate the beginning of settler-colonialism. Tarren Andrews, for example, dates it to the Medieval era. 1492 represents a particular type of rupture as well. I choose 1600 because of the sheer volume of “commerce” moving across the Atlantic in toxic triangles and quadrilaterals by this point in time. Furthermore, there are numerous ways to name both Indigenous connections to place while recognizing shared evolutionary history, without destabilizing Indigenous connections. Indigenous Peoples are connected to their homelands in an indissoluble, irreducible way, and in ways very different than European settler-colonists. I do not see this as a contradiction to the shared human evolutionary history of ancient migration of everyone from the Great Rift Valley in what is now called eastern Africa. People walked from there all over the world, and became some of the first humans to relate to all sorts of different lands and waters, to become indigenous to those places. As the timescales are vastly different (10,000 years ago vs. 1000 years ago), and “time immemorial” refers to “the time we collectively remember”. Numerous indigenous groups on Turtle Island, for example, do not have a collective memory of the trek from Africa and their stories begin with them located en situ. Though the collective trek happened, sharing that information with Indigenous Peoples whose origin stories state otherwise should not be used to displace their claim of being aboriginal to their homelands, instead, only used to recognize the ultimate kinship among humans (homo sapiens) making all people deserving of mutual recognition as persons. Personhood, and relatedly, belonging through kinship or social circumstances, has not always been afforded to people of African descent, both within and outside of some Indigenous communities. ↩

-

Hayes, Kelly. “How to Talk about #NoDAPL: A Native Perspective.” Truthout, October 28, 2016. Retrieved from: https://truthout.org/articles/how-to-talk-about-nodapl-a-native-perspective/. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

As an author who primarily identifies ethnically as a person of African descent, I will use personal or collective pronouns when speaking about Black people and our experience. Like many “African-Americans”, I have ancestors who are “Native-Americans.” That history and those connections were not kept alive in my immediate or extended families. Therefore, I employ the third person singular and plurals when referring to indigenous people and their experiences. ↩

-

A listing of these bulls includes Papal Bull Dum Diversas 18 June, 1452, The Bull Romanus Pontifex (Nicholas V), January 8, 1454 and The Bull Inter Caetera (Alexander VI), May 4, 1493. Later expansions of these bulls include the Treaty of Tordesillas, June 7, 1494, the Patent Granted by King Henry VII to John Cabot and his Sons, March 5, 1496, The Requerimiento, 1514. https://doctrineofdiscovery.org/. ↩

-

Dum Diversas, 1452. ↩

-

Miller, Robert J., et al. Discovering indigenous lands: The doctrine of discovery in the English colonies. Oxford University Press, 2010.The “foundational US Indian policy as stated in 1783 by General (and later President) George Washington was the ‘Savage as the Wolf.’ As he explained to Congress, the expectation of the United States was that Indian lands and resources would naturally be acquired by Americans. Washington compared Indians to animals that would naturally retreat and lose their lands to the advance of the United States. The US government operated under this policy until the 1960s.” (page 66). ↩

-

King with velez, “On the Black Shoals: Part 2”. ↩

-

Beloved Community, https://becomingbelovedcommunity.org/doctrine-of-discovery. ↩

-

Kivel, Paul. Living in the shadow of the cross: Understanding and resisting the power and privilege of Christian hegemony. New Society Publishers, 2013. ↩

SUGGESTED CITATION

Sarah Nahar, "Part 3: Using the Doctrine of Discovery to Foreground an Analysis of Settler Colonialism," Doctrine of Discovery Project (10 May 2023), https://doctrineofdiscovery.org/blog/river/settler-colonialism-analyized/.

Donate today!

Open Access educational resources cost money to produce. Please join the growing number of people supporting The Doctrine of Discovery so we can sustain this work. Please give today.